Falco Feeds extends the power of Falco by giving open source-focused companies access to expert-written rules that are continuously updated as new threats are discovered.

Although most companies make the switch to containers for reasons other than security, eventually they will wonder about exactly how security will fit in and whether their existing security mechanisms will translate to container-focused deployments. To help answer some of those questions, we thought we'd look at some of the Docker security benefits and challenges containers bring to the software ecosystem.Although there are a variety of container formats and distribution systems, to limit the scope of the discussion most of the examples we list will focus on Docker. However, for the most part these topics apply not only to Docker security but more generally to any container-based software deployment.We'll cover these four topics:

- Verifying Container Image Integrity and Authorship

- Scanning Container Images For Known Vulnerabilities

- Reducing the Attack Surface for Containerized Applications

- Host-level Docker Security in Deployments 4 Features of Containers that Help and Hurt Docker Security: verifying, scanning, attack vector and host security Click to tweet

Verifying Container Image Integrity and Authorship

It's important to be able to verify that the contents of an image have not been changed since a package was created. It's equally important to verify that an image came from a specific vendor and not a third party masquerading as that vendor.Luckily, Docker supports both. As of v1.12, Docker image IDs are a digest (usually sha256) of a configuration object that names all the layers that make up the image along with author/configuration information. It's not possible to change the contents of an image without changing the digest/image ID.For example, let's look at the library/busybox Docker image:$ docker inspect --format="{{.Id}}" library/busybox:latest

sha256:7968321274dc6b6171697c33df7815310468e694ac5be0ec03ff053bb135e768

If you fetch the configuration object with that digest, you'll get the configuration object for that image. I'm skipping some other steps like requesting an auth token and pretty-printing the output for readability:$ curl https://registry-1.docker.io/v2/library/busybox/blobs/sha256:7968321274dc6b6171697c33df7815310468e694ac5be0ec03ff053bb135e768 | jq

{

"architecture": "amd64",

"config": {

"Hostname": "4cfe65ad68c6",

"Domainname": "",

"User": "",

"AttachStdin": false,

"AttachStdout": false,

"AttachStderr": false,

"Tty": false,

"OpenStdin": false,

"StdinOnce": false,

"Env": [

[...]

}

And if you compute the sha256 of that configuration object, it matches the image id:$ curl https://registry-1.docker.io/v2/library/busybox/blobs/sha256:7968321274dc6b6171697c33df7815310468e694ac5be0ec03ff053bb135e768 | sha256sum

7968321274dc6b6171697c33df7815310468e694ac5be0ec03ff053bb135e768 -

Docker also has a mechanism that allows image publishers to sign images with the private half of a keypair. At download time, clients can verify the signature with the public half of the keypair. Registries like Docker Trusted Registry and Artifactory both support this mechanism.Combined, these features ensure that the software you download is the same version as the software that was originally published.

Scanning Container Images For Known Vulnerabilities

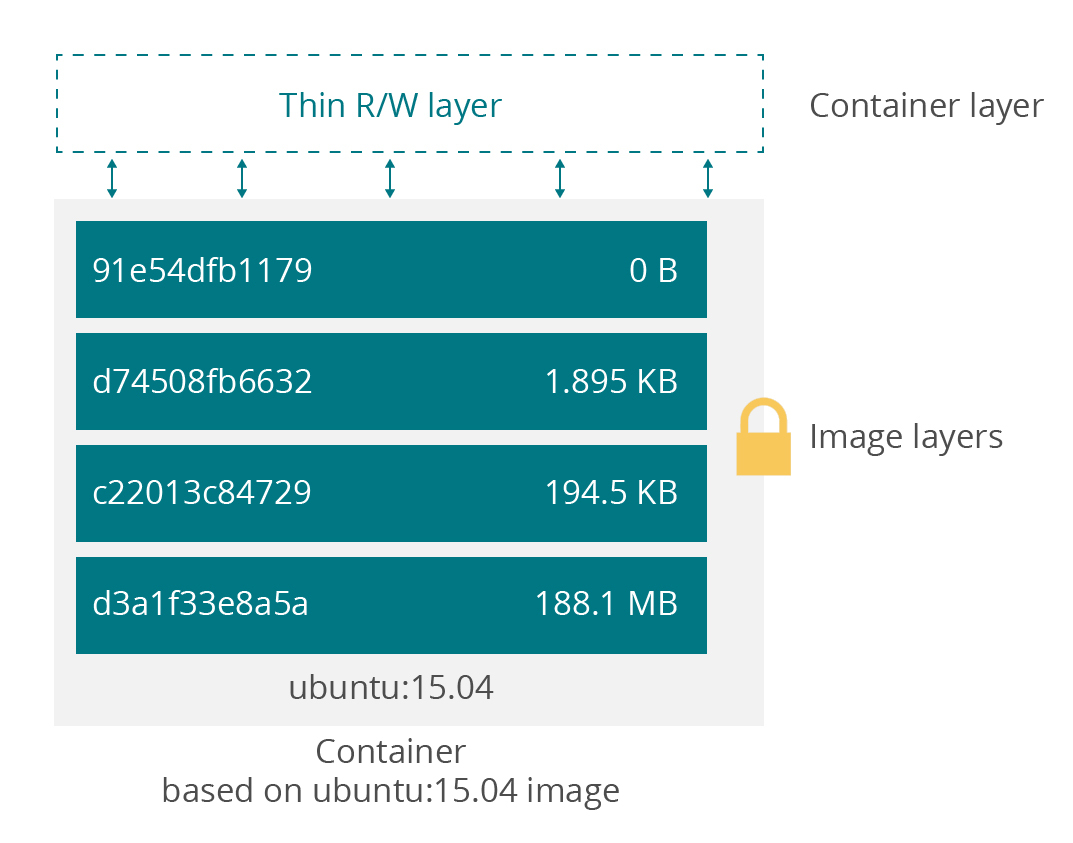

At this point, you can safely download an image and know that that it matches the originally published image and is from the publisher. However, you don't know if the software itself has vulnerabilities that can be exploited by an attacker like Heartbleed, POODLE, etc.To fill this gap, many image registries provide container image scanning capabilities than scan image contents looking for versions of software known to have security vulnerabilities. Quay.io and Docker both provide image scanning features.Remember that a container image has the main software package as well as all supporting software and libraries as an isolated collection, assembled as a series of layers. The first line of all Dockerfiles is a FROM line that starts with an existing image and then makes changes to it based on the commands in the Dockerfile.

This becomes both an advantage and disadvantage. If a given layer e.g. debian:x.y.z contains a version of OpenSSL that is susceptible to Heartbleed attacks, you can identify all upstream software with vulnerabilities simply by looking for images built on the debian:x.y.z image. You don't have to re-scan the debian:x.y.z layer repeatedly for each image that uses it.However, the stack of layers is frozen at image creation time and will not automatically pick up updated copies of supporting libraries, etc. until the image is rebuilt. You can't simply swap out the debian:x.y.z layer with an updated debian:a.b.c layer, as that would change the image's digest, invaliding the image.The consequence of this is that you as the image maintainer are now responsible for tracking vulnerabilities in your own software as well as all its dependencies. So if your software uses OpenSSL, libcurl, and the Java JRE, you can't rely on OS-level security updates any longer: you have to monitor each of these libraries for vulnerability notifications and rebuild your Docker image every time they have a security update.

Reducing the Attack Surface for Containerized Applications

At this point, you have known images from known vendors that are free of known defects. What about as yet undiscovered vulnerabilities? Is there a way to reduce the actions a software package can take so even if it is compromised an attacker's ability to wreak havoc is limited?Containers themselves provide a first level of protection. An inherent part of containerizing an application involves creating namespaces and cgroups that isolate the software running in the container from the resources on the host or other containers. Once isolated, the software's visibility and resource usage is limited to itself and its child processes. This has obvious security advantages–for example, if someone exploits a Node.js vulnerability on a containerized application to gain remote execution privileges, it can only affect resources within the container and not the entire machine.Of course, the isolation that containerization provides is useful, but a quick glance at the available system calls on Linux show many possible ways in which a containerized application could indirectly access host resources. For example, a containerized application could use the setns() system call to immediately escape back to the host namespace and access host resources, or use ptrace() to attach to processes running outside the container.This is where tools like seccomp and its successor seccomp-bpf come in. Seccomp is a mechanism in the Linux kernel that allows a process to make a one-way transition to a restricted state where it can only perform a limited and fixed set of system calls.seccomp-bpf is an extension to seccomp that allows specifying a profile (filter) that is attached to the process and applied to every system call.In a SELinux, Seccomp, Falco, and You: A Technical Discussion we showed detailed examples of how to use seccomp and seccomp-bpf to restrict the system calls that a process can perform.In order to enhance security, Docker uses seccomp-bpf to isolate containerized applications. Docker launches processes with a seccomp profile that disables 44 system calls, preventing their use. Examples of disabled system calls are mount (mounting new filesystems), reboot (reboot the host), setns (change namespaces), etc.

Host-level Docker Security in Deployments

Although containerization and seccomp significantly reduce the likelihood that a software exploit will result in host access, escapes are still a possibility. For example, Docker recently fixed an exploit that allowed a malicious process inside a container to utilize an open file descriptor from the host to gain access to the host filesystem.This is where traditional host-based IPS/IDS systems come in to assist your Docker security strategy, including:

- Mandatory Access Control systems like SELinux, AppArmor, Tomoyo, etc.

- Auditing systems like Auditd, Sysdig Falco, etc.

- Host Intrusion Detection Systems (HIDS) like Tripwire, Aide, Samhain, etc.

We've already discussed MAC and Auditing systems in a SELinux, Seccomp, Falco, and You. Let's briefly describe the goal of HIDS systems like Tripwire/Aide and how they are affected by containerization.HIDS systems strive to detect intrusions by monitoring the state of the host's filesystem. The principle is that an attacker's actions will result in changes to files that can be detected when compared to a prior state of the system.When first installed and started, HIDS systems scan all files on the host filesystem and store cryptographic hashes for each file in an object database. Periodically, the systems rescan the files and report differences as possible indications of an intrusion. For example, if an attacker gained access to a host and installed a rootkit below /var/lib/mysql/i-am-a-hacker, the HIDS system would note the addition of /var/lib/mysql/i-am-a-hacker and report that as a suspicious action.Containerization has both positive and negative benefits to HIDS systems. Generally, monitoring a host is easier when it is changing less often. In a containerized environment, the host is generally only running the container engine software and not any additional applications. This results in a more static system that is easier to monitor.However, the containerized applications themselves are a complete blind spot to HIDS systems. Since a container contains a self-contained file tree devoted to that container, it must be created from scratch when the container is started. Additionally, the ephemeral nature of containers implies that the container (and its file tree) can come and go at will. A HIDS system that tried to monitor /var/lib/docker would either never finish scanning the contents, or go crazy trying to report the differences, or both.To help avoid this blind spot, security systems need to be namespace-aware so they can switch to the context of the containerized application and apply host-level policies in that context. Sysdig Falco is one example of this. Its policies work equally well inside and outside of containers, as it changes namespaces on the fly to switch to the context of each container before using its ruleset to identify suspicious activity. For example, Falco's default ruleset has a rule "Write below binary dir" that looks for attempts to write files below directories like /bin, /sbin, etc. If a container were compromised and an attacker tried to install a rootkit below /bin/i-am-a-hacker, although the host file would be somewhere below /var/lib/docker/…., Falco uses setns() to switch to the namespace of the container and notices the attempt to write below /bin.

Summary

In this post, we've discussed several ways in which containers affect the software deployment and management lifecycle, specifically in the context of Docker security. They include:

- Mechanisms to ensure software integrity and authorship

- Images-as-layers and how that helps and hurts vulnerability scanning

- Ways in which containerization reduces the attack surface for exploits

- How host security needs to adapt to containerized software deployments

If you want to know more on our view of the Docker security landscape, we were at FOSDEM 2017 with WTF my container just spawned a shell, these are the slides of the talk:

WTF my container just spawned a shell! from Sysdig

And if you have some time, at Sysdig CCWFS I presented How to Secure Containers, if not, check out Sysdig Falco YouTube playlist for short videos!