Falco Feeds extends the power of Falco by giving open source-focused companies access to expert-written rules that are continuously updated as new threats are discovered.

The IT world was put on its heels this past week as two of the most significant hardware exploits were announced for CPUs from Intel, ARM, AMD, IBM, and others. Early estimates state that as many as 3 billion devices have this flaw (don't worry, your Apple II and C64 is safe). As there often is with a vulnerability of this magnitude, there's a ton of noise associated with the problem, which makes it difficult for the average IT professional to get to the facts. So let's step back from the hyperbole, and break down exactly what the problem is, and how it affects the day to day life of the average IT professional.

\r\r

What's the problem?

\r\r

Two separate but related vulnerabilities were announced this past week, Meltdown and Spectre.

\r\r

Meltdown

\r\r

Meltdown exploits the normal isolation between user space memory and kernel space memory by exploiting speculative execution of CPUs (more on speculative execution in a minute). With the Meltdown attack, an attacker could read parts of the kernel memory and potentially exploit a system. On older 32-bit systems (remember those), the kernel space was always the first 1GB of memory and the remaining 3GB (if you had that much) was for user space. On modern 64-bit systems, this kernel space attack is mitigated by placing the kernel space at a random location on boot. Unless the address of the kernel space leaked, attackers had no knowledge of where the kernel space was placed in memory. Meltdown allows the attacker to find out the address of the kernel space memory (or Kernel Page Table), and thus attacks on the kernel space can be executed once again. AMD CPUs do not appear to be vulnerable to this issue, whereas virtually all Intel chips are impacted and only a few ARM chips are vulnerable.

\r\r

Spectre

\r\r

Spectre is also about attacking isolation in a system, but this time between applications. A Spectre based attack seeks to read the memory space of another user application, thus compromising the data that application might be using. This data could include information such as user data, passwords, encryption keys, etc. This attack also exploits the concept of speculative execution in the CPU. The Spectre exploit appears to affect all CPU manufacturers.

\r\r

Speculation execution

\r\r

Modern CPUs use a number of techniques to speed up execution. They've had the capability of executing multiple operations at the same time for years now, and this is often used to speed up execution. Speculative Execution is just that. While CPU is executing an operation, it will load subsequent operations into cache and execute them if there isn't a dependency on the current operation. This speculates that the current operation will succeed. The problem with this approach is that if the current operation fails, the CPU doesn't clean up after (or retire) the speculatively executed commands and any data in the CPU cache. This allows an attacker to have an malicious operation executed that loads sensitive information into the cache, and then later get access to that sensitive cached information (because it's not retired).

\r\r

This is of course a very high level explanation of the problem. For a more in depth explanation, you can find papers on both Meltdown and Spectre. It's also worth noting that Meltdown focuses on breaking (or melting) the boundary between kernel space and user space, and Spectre focuses on breaking the boundary between applications in user space (think of a user installed malware reading your Firefox saved passwords, or a website running Javascript being able to read site data from other sites).

\r\r

How do you fix it?

\r\r

Fortunately, the exploit was discovered several months ago, and vendors have been working furiously to ensure patches were available once the bug was made public. Because speculative execution is a feature of the CPU, and replacing all CPUs is virtually impossible, operating system vendors needed to fix the problem at the kernel level. You can find a comprehensive list of patches and advisories on the Meltdown website.

\r\r

For convenience here are a few links for common operating system vendors:

\r\r

\r\r

If you're interested in a more technical explanation of how Meltdown was mitigated (for Linux at least) you can read about Kernel Page Table Isolation (KPTI). Spectre is actually a class of exploits, and mitigation is a combination of kernel level patches and recompiling applications with a patched compiler.

\r\r

What's the impact of the patches?

\r\r

Unfortunately the mitigation of Meltdown and Spectre carries with it the possibility of significant system slowdown. Linux Weekly News had a good write up of Meltdown's patch initially called KAISER (now called KPTI). While the details are outside of the scope of this blog post, the long and short of it is that every syscall or interrupt now has had several hundred CPU cycles added to them.

\r\r

Initial estimates were that the patches for Meltdown & Spectre would introduce between 5% to 30% CPU performance impact. Our friends at Red Hat ran benchmarks and found that that there was anywhere between 1% to 20% performance impact for applications running on bare metal. In regards to virtual machine performance, Red Hat states:

\r\r

We expect the impact on applications deployed in virtual guests to be higher than bare metal due to the increased frequency of user-to-kernel transitions.

\r\r

Red Hat has found that database workloads are more likely to see a measurable negative impact of 8-19% when it comes to CPU performance. Some users are starting to report these problems in their testing or on production systems. Here's a roundup of some of the issues.

\r\r

- \r

- Riak and Redis showing a 50% and 40% performance impact respectively. \r

- Postgres benchmarking with pgbench shows a 23% degradation in performance. \r

- Epic games credits patches with service stability problems. \r

- The Spectre patch applied to AWS hosts showing 40% performance hit for Kafka. \r

- AWS Elasticache showing 30-40% performance impact. \r

\r\r

While these are anecdotal stories, it does appear that these patches are having real world performance impacts. In a few of these cases, the host operating system is patched, but the guest is not. If our friends at Red Hat are right, performance could degrade even more once the guest operating systems are patched.

\r\r

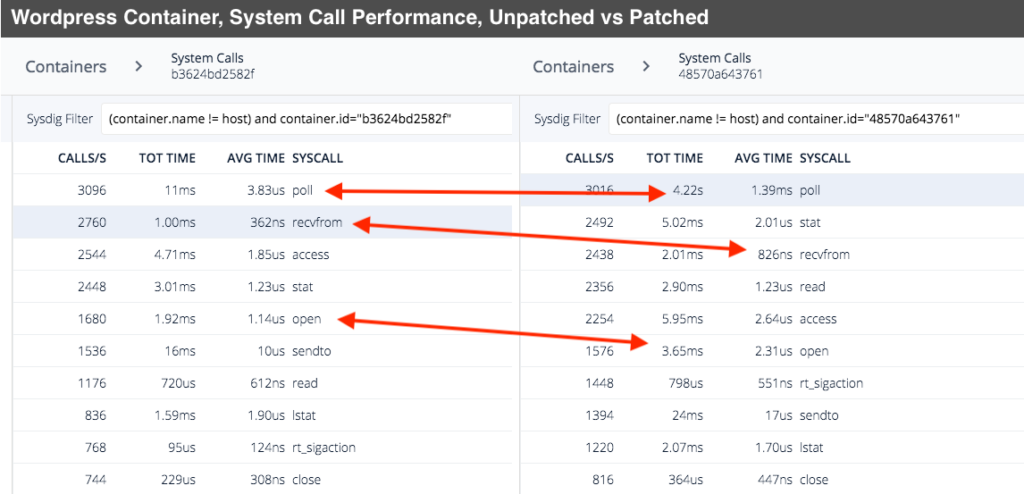

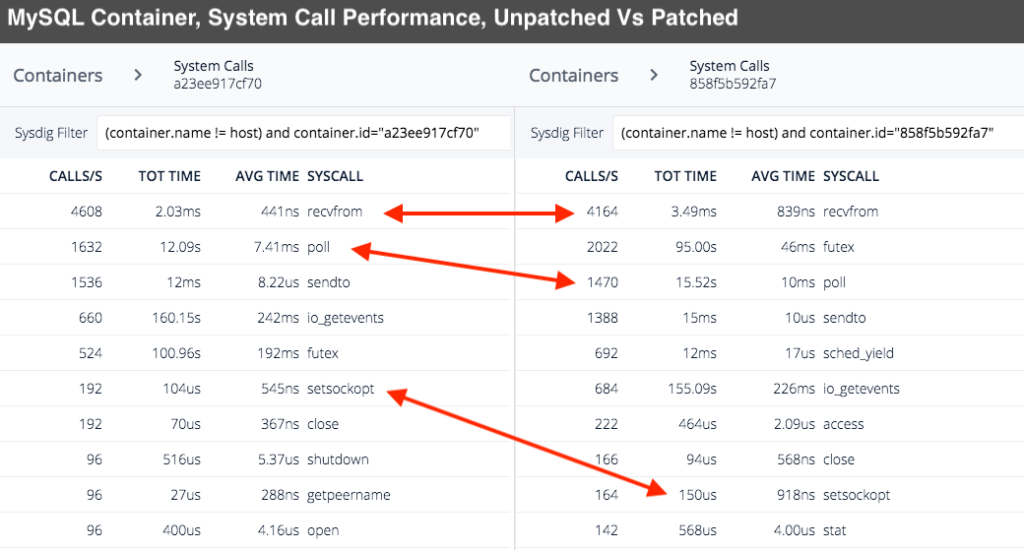

Using our open source system call capture tool, Sysdig Inspect, we took samples from a WordPress application that uses a MySQL backend. Both applications are containerized with Docker and were running on the same Ubuntu 16.04 host. The unpatched kernel was running Ubuntu's kernel version 4.4.0-87-generic while the patched version was 4.4.0-108-generic. The captures were filtered down to see how much time was spent in each system call for the individual container. This is by no way a scientific exercise but it does show that there is a dramatic increase in time spent in some system calls.

\r\r

\r\r Use open source @Sysdig to measure the system impact of #meltdown/#spectre Click to tweet \r\r

\r\r

While some of these system calls only add a few microseconds, some calls have went from microseconds to milliseconds. On a loaded system, these small increases in execution time will add up quickly. Needless to say, comparing Sysdig captures confirms slow down inside of system calls (as the kernel maintainers expected) as a result of these patches.

\r\r

Mitigation of impact

\r\r

By now you're probably wondering what can be done, if anything, to mitigate the performance impacts of Meltdown/Spectre patches. If you're running in a cloud provider, there's not a lot you can do. Many have already began mandatory host reboots to take the kernel patches to fix these problems. You will most likely see performance decline for IO intensive applications with just the host being patched. There are however some practical steps you can take to make sure your impact is lessened.

\r\r

- \r

- Ensure proper monitoring is in place – It should go without saying, but you'll want to make sure all of your applications have the appropriate monitoring in place, especially in lower environments where you will want to determine the impact of these patches on your application. This is also a good time to make sure you can monitor application response time metrics. You might be monitoring standard metrics like CPU, RAM, and IO already, but you'll also want to make sure you can see into your application to see how quickly it's responding to requests. This is especially important given the slowdown in system calls that is being seen, which will translate to degraded application performance. \r

- Ensuring alerting is in place for key metrics – Now is a good time that you have alerts in place for key metrics that are impacted by these patches, specifically alerts for response time / service latency. \r

- Double check auto scaling settings – For applications that can scale horizontally, you should already be running them in your cloud provider's auto scaling mechanism. If not, now is the time to get those instances into an auto scaling group. If you are already using auto scaling groups, you'll want to ensure your groups are not maxed on capacity. If you're using a container scheduler such as Kubernetes, you'll want to make sure the appropriate Deployments have auto scaling configured. In addition you'll want to make sure your Kubernetes cluster can automatically scale up as well. \r

- Determine if you need to vertically scale instances – If your instances appear to be overwhelmed, or if the patches have ate up the overhead you had allocated, you may want to evaluate the feasibility of changing your instance type. All cloud providers make this a fairly easy process. \r

- Disable the kernel fixes implemented by the patches – If you find performance is too degraded, you can disable the fixes introduced by the patches. Red Hat provides a good write up of the steps required to disable the fixes via boot options or via debugfs controls. If running in a VM, you'll still inherit any degraded performance from the underlying host system. \r

\r\r

Summary

\r\r

While there is much hype and hyperbole surrounding the Meltdown and Spectre exploits, it's not without good cause. It's not a far stretch to say that this is one of the most widespread exploits of our time (so far). Depending on the workload you almost certainly will pay a penalty in CPU performance, and maybe even a financial penalty if your application requires more compute resources.